This post from George Chatzigeorgiou, a moral premise fan from Greece whose material I have posted before.

=====

While watching films and noticing how the moral premise works in them, I've found that in many good films, although there is a moral premise, it doesn't have the fully realized structure that is presented in the book, mainly plot arcs and moments of grace for main characters besides the protag. For example, the kind of films some call "character study" do not have full arcs for secondary characters ("Taxi Driver" for instance).

Thus, I've compiled a set of general rules which I think can be applied in just about any film with a good moral premise. I find these rules very freeing, cause they help me apply a moral premise without feeling confined by a highly rigid, "idealized" structure that serves well as a general guide and as a general template, but I don't think it's necessarily meant to be fully realized. So let me know what you think, will you? (In my general rules I've also included Blake Snyder's advice that the movie's theme should somehow be stated through dialogue during the set up.) I also think that these rules serve as a simplified summary of what the moral premise's all about.

Summary of the rules of a good moral premise:

1) Have a moral premise as the movie's thematic core structured as: [Virtue] leads to [success], but [vice] leads to [defeat].

2) Make the theme crystal clear by including a distinctive theme statement (preferably in the set up), by infusing the movie with "moments of grace" (beats which awaken in the minds and hearts of the audience what the movie is really about), and by exhibiting both sides of the moral premise, as well as each side's consequences.

3) Keep the moral premise consistent throughout the movie and don't betray it. This, in short, means that any character choosing to practice the virtue side should ultimately experience success, while any character choosing to practice the vice side should ultimately experience defeat.

George

Discussion and analysis of screenplays, scripts, and story structure for filmmakers and novelists, based on the blogger's book: "THE MORAL PREMISE: Harnessing Virtue and Vice for Box Office Success".

Monday, September 28, 2009

Wednesday, July 15, 2009

Top 10 Secrets of Successful Screenplays

As I was preparing for TIGER'S HOPE, CBS organizers asked me to present a talk at a local film production expo—Michigan Makes Movies EXPO. My workshops are based on my book: "The Moral Premise: Harnessing Virtue and Vice for Box Office Success", that Will Smith says is "the most powerful tool in his new toolbox." When I gave the organizers the title of my talk, they weren't sure they wanted to use that title, because it would confuse people. "What is this guy doing talking about a moral premise at a film expo? I mean it's Sunday, but isn't morality for Sunday morning at a Church?" So, I changed the title to "Top 10 Secrets of Successful Screenplays." Of course, the content was identical, except I put ten magenta and yellow numbered buttons throughout the presentation. "There's more than 10, here." I blurted out.

As I was preparing for TIGER'S HOPE, CBS organizers asked me to present a talk at a local film production expo—Michigan Makes Movies EXPO. My workshops are based on my book: "The Moral Premise: Harnessing Virtue and Vice for Box Office Success", that Will Smith says is "the most powerful tool in his new toolbox." When I gave the organizers the title of my talk, they weren't sure they wanted to use that title, because it would confuse people. "What is this guy doing talking about a moral premise at a film expo? I mean it's Sunday, but isn't morality for Sunday morning at a Church?" So, I changed the title to "Top 10 Secrets of Successful Screenplays." Of course, the content was identical, except I put ten magenta and yellow numbered buttons throughout the presentation. "There's more than 10, here." I blurted out. The organizers were hoping for 500-600 to show up. Instead 1,500 crammed the aisles of the Rock Financial Showplace in Novi, just 3.6 miles from my driveway. It's closeness to my home was good, because time got away from me (we went to a late Mass), and I found myself rushing to the site and the "greenroom" trailer, flying a "Welcome Guest Speakers". When my handler (Steve) guided me through the hall for my 3:30 talk, I could hardly find a place to walk for all the people in line behind several of the breakout room doors. (!). They set me up with a room that had crammed into it about 120 chairs. Be the time I started all the chair were filled, and 1/2 way through the SRO crowd were turning people away.

The organizers were hoping for 500-600 to show up. Instead 1,500 crammed the aisles of the Rock Financial Showplace in Novi, just 3.6 miles from my driveway. It's closeness to my home was good, because time got away from me (we went to a late Mass), and I found myself rushing to the site and the "greenroom" trailer, flying a "Welcome Guest Speakers". When my handler (Steve) guided me through the hall for my 3:30 talk, I could hardly find a place to walk for all the people in line behind several of the breakout room doors. (!). They set me up with a room that had crammed into it about 120 chairs. Be the time I started all the chair were filled, and 1/2 way through the SRO crowd were turning people away. Now, I don't think this SRO crows was "me" or my particular presentation (there were numerous presentations all at once)... although I took notice that no one was sleeping at least by falling out of their chair. I think the crowd was more evidence that the film industry in Michigan has the potential of popping out all over. There is a raw enthusiasm here for filmmaking.

Now, I don't think this SRO crows was "me" or my particular presentation (there were numerous presentations all at once)... although I took notice that no one was sleeping at least by falling out of their chair. I think the crowd was more evidence that the film industry in Michigan has the potential of popping out all over. There is a raw enthusiasm here for filmmaking.The day of the expo I read a web news report of a man at a fair nearby, who was impersonating Robert DeNiro. Guess what, the man was no impersonator. About every other day that I'm out on the road I pass a movie trailer or make-up trailer.... with California plates. And when we decided to use the RED camera on Tiger's Hope (the latest technology that Hollywood has embraced) I was surprised to discover a supply of perhaps 12 in the city for rent. That's really significant. (But I think the cheapest rates are still in CA

There's a thirst for knowledge, and the Expo this past Sunday was one of those great events where for $20 attendees could gain a huge amount of knowledge in a very short period of time. The best students are enthusiastic and hungry students. And they were in large supply on Sunday.

At the end of my one-hour talk (the workshop is actually 16 hours, so these 1 hour gigs are a challenge, especially with the multiple movie clips I use to demonstrate the moral premise) I announced that the books were available on line at Amazon.com or MoralPremise.com, and that I had a box of books with me, but I wouldn't be able to sign them personally until after the next session in which I was scheduled to appear on a pitch panel. Well, before I could unplug my laptop, 18 books disappeared from the box and $20 bills were being stuffed into my hands or Steve's. After the second session on pitching, I had a line up of people to talk to, and a few more books to distribute, and when I left the building, the green room was being towed out of an empty parking lot.

At the end of my one-hour talk (the workshop is actually 16 hours, so these 1 hour gigs are a challenge, especially with the multiple movie clips I use to demonstrate the moral premise) I announced that the books were available on line at Amazon.com or MoralPremise.com, and that I had a box of books with me, but I wouldn't be able to sign them personally until after the next session in which I was scheduled to appear on a pitch panel. Well, before I could unplug my laptop, 18 books disappeared from the box and $20 bills were being stuffed into my hands or Steve's. After the second session on pitching, I had a line up of people to talk to, and a few more books to distribute, and when I left the building, the green room was being towed out of an empty parking lot.

Monday, June 29, 2009

The Dramatic Center

Recently I was asked by two editors to write a chapter for "their" book — a book written by others, but with the editor's names on the cover. I've never thought this was a very good idea. And sure enough, this was one time when the more I discussed the chapter with them (by email) the more I felt they were typical charlatans. What tipped the scale for me was when the chapter that I wrote for them for free, they refused to allow my book's website URL in my bio. Enough. A couple of the values I value are fairness and generosity. The editors and I had a conflict. The essence of all good stories. So I told them: "End of story. No, you can't use my essay."

So, here it is, I'm at least generous, but not a sucker.

----

The Dramatic Center - the Conflict of Values

The dramatic center of any story is the conflict between two opposing values. Discovering what those values are, which drive your protagonist and antagonist against each other, is critical to knowing what your story is about, and how it begins and ends.

When writers come to me for help because their story doesn’t resonate, often it’s because the conflict is not centered around a central opposing pair of values. Many writers will construct a story around a physical conflict, but fail to realize that for the story to organically connect with an audience the physical conflict must be rooted in opposing psychological mind-sets or moral values. Never forget that all physical or visible action begins with a psychological decision, and that decision is rooted in a value. Stated another way, no action can occur without first being motivated out of moral ideals.

Consider that 9-year old Toby wants a dog, but his mother has said, “No!” The explicit premise or physical storyline might be: “Toby tries to persuade his Mom to let him have a dog.” That’s what the movie is “about.” But what is it “really about?” What are the values that Toby and his Mom each hold that cause them to be in conflict? Is it that Toby loves dogs and his Mom hates them? Not likely. You have to go deeper and examine the human conflict in terms of universal values, or the things people hold true regardless of culture.

For example, Toby and his Mom may be in conflict over the difference between slothfulness and orderliness. Mom knows Toby pretty well and she doesn’t think her son will pick up the backyard after a dog’s droppings, and Mom, in the same backyard, is trying to hang clean laundry on the line to dry. Yikes! Or, perhaps the story is about keeping promises vs. breaking promises. Toby promises to take care of his messes, but Mom always ends up picking up after him.

The other dimension of such conflicts is that society, in general, will value one of these traits as morally good (cleanliness or keeping promises) and the other as morally bad (slothfulness or breaking promises). The values that allow society to make progress are called virtues, and those that degrade society are called vices. Thus, the story of Toby and his Mom is really a story of moral values, or to be precise it’s about a moral premise. While the physical or explicit premise is about taking care of the dog, the psychological or implicit premise is about taking responsibility. And it is those psychological values that drive the protagonist and antagonist to conflict and thus create drama.

Once you figure out what the essential conflict in values is, you’re story will write itself. Suddenly you will know what Toby’s character flaw is (he’s a pig pen and he loves it) and what Mom’s character virtue is (she keeps a clean house and she loves it). And now you can write out what is called the story’s moral premise around which every creative aspect of the story will flow. It could be something this simple as this: Slothfulness leads to Loss; but Orderliness leads to Gain. And the question for your plot is this: Does Toby’s values change or do Mom’s values change? And what are the physical consequences?

Understanding the heart of the moral conflict in your story, and how the consequences flow from the virtues and vices involved, will forever liberate you from writer’s block.

EXERCISE

Let’s look at one of those great stories you’ve started but could never finish. Take one out of that dull gray filing cabinet in the corner, and let's see if we can fix it.

Process the following steps iteratively. That is, repeat them until the answers to each step are in sync with the others, and when repeating the questions your answers do not change.

1. Revisit a story that you’ve given up on. Scan enough of it get it fresh in your mind.

2. Write down the protagonist’s physical goal. Make sure it’s something the audience can visibly see and root for, or against.

3. Write down the value that ultimately drives the protagonist successfully toward that goal. If your story is redemptive, this must be a strength or virtue. If the protagonist is a “bad guy” the value is a weakness or a vice.

4. What is the value opposite the value you wrote down in No. 3? Your answer to this question should be the motivating value of the antagonist. Is it? If not, fix it.

5. Write down the physical consequences that naturally (in reality) follow the practice of the values you identified in Questions 3 and 4. Is your story consistent to this “truth and consequence?” Or is the consequence contrary to the vice or virtue practiced?

Now, a word of caution. Understand the difference between your voice as the screenwriter or filmmaker and the voice of the story. They are not necessarily the same, especially when it comes to ironic endings. CHINATOWN is a good example. The story’s voice says that evil wins, but the filmmaker’s voice rejects the evil, and claims the movie a tragedy.

6. After thinking about the story you’ve dragged out of the dust pile, see if you can create a true moral premise statement for the story that you want to tell. It should be structured like this:

[a moral vice] naturally leads to a [detrimental consequence] but

[a moral virtue] naturally leads to a [beneficial consequence].

[a moral virtue] naturally leads to a [beneficial consequence].

Formulating such a statement will tell you everything you need to know about your story and the motivation of all its characters.

8. Repeat these steps until they are in harmony. Now rewrite the screenplay. You’ll love it.

Sunday, May 31, 2009

The Moral Premise in Burbank

This is silly, but I just got an email from professor and author Drew Yanno who partnered with me during a recent story consulting job with Will Smith. See this post.

Here's what Drew, who authored "THE 3RD ACT" wrote:

One of my former students who lives in Hollywood now sent me the attached picture that he took with his cell phone in the Barnes & Noble in Burbank.I told Drew that unfortunately neither his book nor mine were going to sell as many as the book between ours titled "Cool Million: How to Become a Million-Dollar Screenwriter" -- although I just noticed on Amazon that "Cool Million" is only selling for $1.86. (Says something.)

He didn't know about the book shown two away from mine. I told him he better read it before he writes his next script! Hope all is well with you.

Drew

Tuesday, April 21, 2009

Morals vs. Ethics

My friend, Jim Lichtman (author of WHAT DO YOU STAND FOR and blogger at www.ethicsStupid.com) and I were discussing how the ins and outs of "moral vs. ethical" principles. Since he lectures and writes a lot on the topic of ethics, I asked him some questions and he provided me with the following answers. I'm posting them here with his permission. I'll not indent it, but here it is verbatim. The questions are mine. Emphasis is Jim's. My comments in [brackets].

=======

How would you explain the relationship between the terms "ethics" and "moral principle"?

Traditionally, there is little difference between “ethics” and “morality” or “moral principle” and “ethical principle.” Although both have a basis in “right” conduct, “‘morals,’ my teacher Michael Josephson points out, “tends to be associated with a narrower and more personal concept of values, especially concerning matters of religion, sex, drinking, gambling, etc.”

When we speak of “ethical values,” we refer to a set of universal values of “right” conduct irrespective of one’s religion or cultural background. Although there may be differences in “morals” I don’t believe I can find any culture or religion where someone does not wish to be treated with respect, honesty, compassion, etc.; which are all considered universal, ethical values.

Josephson says that “Moral duty refers to the obligation to act or refrain from acting according to moral principles. Moral duties establish the minimal standards of ethical conduct. Moral duties require us to do certain thing (be honest, fair, accountable) as well as to not do other things (harm others, treat them disrespectfully).”

Whereas, “Moral virtue goes beyond moral duty to a higher level of moral excellence (generosity, bravery). Moral virtues are aspirational rather than mandatory. We ought to be charitable, temperate, humble and compassionate,” Josephson says, “however, it is not unethical if we are not, so long as we do not violate the obligation not to harm others.”

There is a difference, as you suggest in your question, between values and principles. “Values” refers to the general belief about something. “Principles” are rules of conduct. i.e. Honesty is an ethical value. It becomes an ethical “principle” when we translate into something like: Tell the truth; Don’t lie, cheat, deceive another.

“Moral relativism” and “Moral absolutes.”

Don’t you remember that scene in The Incredibles where Mr. Incredible explains to Buddy Kant’s Categorical imperatives: the moral character of an action is determined by the principle upon which it is based, not the consequences it produces? [I didn't remember the scene, so Jim told me this was a joke. oh.]

Buddy argued that he could justify his actions based on his own “relative” set of moral values. Thus, whenever a projected consequence did not suit him, he would change his own rules. He wanted to fight crime with Mr. Incredible who turns around and says, “I work alone, kid!” So, Buddy becomes a “bad” guy, instead.

(I think this scene got cut from the final film.... too long on dialog.)

However, Kant contends that ethical obligations are “higher truths” or “moral absolutes” which must be obeyed regardless of the consequences. i.e. Always tell the truth! On that basis, if the Nazis come knocking on your door (assuming you’re not a Nazi) asking where Ann Frank is and you know, you have to tell them. Self-righteousness is a form of “moral absolutism.” [I grew up calling Jim's "moral absolutism" legalism. It easily could have turned me away from Christianity, but I saw the problem as man's selfishness, not God's grace to give us laws that were good for us. More at the bottom of this post.]

“Moral relativism” places all the cards on one side of the table, and allows whoever holds the cards, to change the rules to suit their own needs.

Both are extremes to be avoided.

According to the Josephson Institute’s Ethical Decision-Making Model:

Hope this helps, Stan. Stay in touch.

---Jim

[The question of the Nazi looking for Anne Frank was interesting. I asked a Catholic theologian. He wrote back the following:

=======

How would you explain the relationship between the terms "ethics" and "moral principle"?

Traditionally, there is little difference between “ethics” and “morality” or “moral principle” and “ethical principle.” Although both have a basis in “right” conduct, “‘morals,’ my teacher Michael Josephson points out, “tends to be associated with a narrower and more personal concept of values, especially concerning matters of religion, sex, drinking, gambling, etc.”

When we speak of “ethical values,” we refer to a set of universal values of “right” conduct irrespective of one’s religion or cultural background. Although there may be differences in “morals” I don’t believe I can find any culture or religion where someone does not wish to be treated with respect, honesty, compassion, etc.; which are all considered universal, ethical values.

Josephson says that “Moral duty refers to the obligation to act or refrain from acting according to moral principles. Moral duties establish the minimal standards of ethical conduct. Moral duties require us to do certain thing (be honest, fair, accountable) as well as to not do other things (harm others, treat them disrespectfully).”

Whereas, “Moral virtue goes beyond moral duty to a higher level of moral excellence (generosity, bravery). Moral virtues are aspirational rather than mandatory. We ought to be charitable, temperate, humble and compassionate,” Josephson says, “however, it is not unethical if we are not, so long as we do not violate the obligation not to harm others.”

There is a difference, as you suggest in your question, between values and principles. “Values” refers to the general belief about something. “Principles” are rules of conduct. i.e. Honesty is an ethical value. It becomes an ethical “principle” when we translate into something like: Tell the truth; Don’t lie, cheat, deceive another.

“Moral relativism” and “Moral absolutes.”

Don’t you remember that scene in The Incredibles where Mr. Incredible explains to Buddy Kant’s Categorical imperatives: the moral character of an action is determined by the principle upon which it is based, not the consequences it produces? [I didn't remember the scene, so Jim told me this was a joke. oh.]

Buddy argued that he could justify his actions based on his own “relative” set of moral values. Thus, whenever a projected consequence did not suit him, he would change his own rules. He wanted to fight crime with Mr. Incredible who turns around and says, “I work alone, kid!” So, Buddy becomes a “bad” guy, instead.

(I think this scene got cut from the final film.... too long on dialog.)

However, Kant contends that ethical obligations are “higher truths” or “moral absolutes” which must be obeyed regardless of the consequences. i.e. Always tell the truth! On that basis, if the Nazis come knocking on your door (assuming you’re not a Nazi) asking where Ann Frank is and you know, you have to tell them. Self-righteousness is a form of “moral absolutism.” [I grew up calling Jim's "moral absolutism" legalism. It easily could have turned me away from Christianity, but I saw the problem as man's selfishness, not God's grace to give us laws that were good for us. More at the bottom of this post.]

“Moral relativism” places all the cards on one side of the table, and allows whoever holds the cards, to change the rules to suit their own needs.

Both are extremes to be avoided.

According to the Josephson Institute’s Ethical Decision-Making Model:

- All decision must take into account and reflect a concern for the interests and well-being of all stakeholders.

- Core ethical values and principles always take precedence over non-ethical values.

- It is ethically proper to violate an ethical value only when it is clearly necessary to advance another true ethical value which, according to the decision-makers conscience, will produce the greatest balance of good in the long run (for the majority of stakeholders, NOT just your own interests). i.e. A friend can’t ask you to lie out of a duty to loyalty.

Hope this helps, Stan. Stay in touch.

---Jim

[The question of the Nazi looking for Anne Frank was interesting. I asked a Catholic theologian. He wrote back the following:

The first edition of the CCC, in no. 2483, would have allowed the deceiving of Nazi soldiers because it stated that "to lie is to speak or act against the truth in order to lead into error someone who has a right to know the truth." In this case, misleading the Nazis about hiding Jews in your house would not be lying because the Nazis do not have the right to a truth which will result in someone's murder. The second edition of the CCC (of 1997), however, revised no. 2483 by dropping the part about "who has a right to know the truth." With this revision, directly lying or deceiving the Nazis would be difficult to justify. Instead, it would be suggested to use evasive speech.I noticed that 2483, and 2484 both end with the qualification "...to lead into error." It seems that lying to a Nazi looking for Jews to kill, thus preventing the killing, also prevents the Nazi from being led into error.

Friday, March 6, 2009

Purchase Pyramid

On the Amazon.com Moral Premise site one reviewer asked what the Purchase Pyramid story structure was. Here's my short explanation and a couple of graphics, and below the Five Stages of Grief, a.k.a. The Kübler-Ross Model.

The "Inverse Purchase Pyramid" model of story telling is based on Allison Fisher's Purchase Funnel. It is upon this model that most romantic comedies are based. You can use this instead of the three Act model, but most effective screenplays overlay the pyramid model on top of the 3 Act model. Imagine an upside down pyramid with the widest part at the top. Divide the the pyramid into five sections with four horizontal lines. Label each area with the five stages that follow. The pyramid breaks the story into the following sequence segments: (1) AWARENESS during which the buyer needs definition of what's for sale; (2) FAMILIARITY during which the buyer needs additional information peaking interest; (3) CONSIDERATION during which the buyer narrows the alternatives for purchase; (4) TRIAL during which the buyer tries out the product; (5) PURCHASE during which the buyer commits. Now apply that to both the guy and the gal as they go through those stages of romance and you've got a winning structure. Here's an emotional roller coaster diagram of how the "5 Acts" might play out:

Five Stages of Grief

Another useful structural tool is the Kübler-Ross Model of how people typically face grief or undesirable events. In my last workshops I have a slide that lists 7 stages, but I'm going to change that back to 5, because 2 of the 7 are unlike the others. So, 5 it is. Here's a graphic that somewhat demonstrates the story algorithm. I say, "somewhat" because the ups and downs of one story dynamic to the next are never the same.

Where does this apply? Anytime you have a character going through a very difficult life change — death of someone close, divorce, loss of income, professional disappointment -- in short a grieving of any kind.

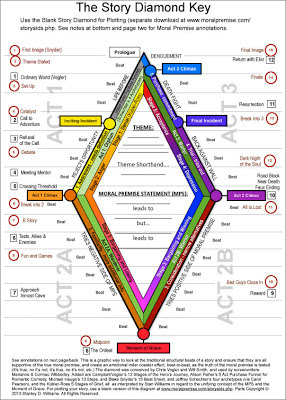

Technique: I recommend structuring your story into the 3 acts and with the help of the 13-16 turning points and sequences as described in this blog, in The Moral Premise, and in other good story technique books (e.g. Hauge, Snyder). And then, layer on the 4 Steps of Grief, if they apply. This will give you more turning points and twists in your story, hopefully positioned where the story is relatively slow. I have, as of this revised post, updated The Story Diamond Writing Aid, where you'll see the five stages overlapping with everything else. The PDF download is linked below. Click on image.

The "Inverse Purchase Pyramid" model of story telling is based on Allison Fisher's Purchase Funnel. It is upon this model that most romantic comedies are based. You can use this instead of the three Act model, but most effective screenplays overlay the pyramid model on top of the 3 Act model. Imagine an upside down pyramid with the widest part at the top. Divide the the pyramid into five sections with four horizontal lines. Label each area with the five stages that follow. The pyramid breaks the story into the following sequence segments: (1) AWARENESS during which the buyer needs definition of what's for sale; (2) FAMILIARITY during which the buyer needs additional information peaking interest; (3) CONSIDERATION during which the buyer narrows the alternatives for purchase; (4) TRIAL during which the buyer tries out the product; (5) PURCHASE during which the buyer commits. Now apply that to both the guy and the gal as they go through those stages of romance and you've got a winning structure. Here's an emotional roller coaster diagram of how the "5 Acts" might play out:

Five Stages of Grief

Another useful structural tool is the Kübler-Ross Model of how people typically face grief or undesirable events. In my last workshops I have a slide that lists 7 stages, but I'm going to change that back to 5, because 2 of the 7 are unlike the others. So, 5 it is. Here's a graphic that somewhat demonstrates the story algorithm. I say, "somewhat" because the ups and downs of one story dynamic to the next are never the same.

Where does this apply? Anytime you have a character going through a very difficult life change — death of someone close, divorce, loss of income, professional disappointment -- in short a grieving of any kind.

Technique: I recommend structuring your story into the 3 acts and with the help of the 13-16 turning points and sequences as described in this blog, in The Moral Premise, and in other good story technique books (e.g. Hauge, Snyder). And then, layer on the 4 Steps of Grief, if they apply. This will give you more turning points and twists in your story, hopefully positioned where the story is relatively slow. I have, as of this revised post, updated The Story Diamond Writing Aid, where you'll see the five stages overlapping with everything else. The PDF download is linked below. Click on image.

Monday, March 2, 2009

Anime and Manga Themes and Premises

Akemi's Post No. 2

(SW's response in Com Box)

Thank you for your response. I'm very excited to have someone who has studied the subject on hand to ask questions of. Please, lets continue this discussion in your blog. I've always felt that I've lacked something in my story telling, and working exactly what it is out on my own has been a pain.

I feel that I found what I’m missing in my studies and your book clarified it. I am quite frustrated studying anime and manga because I’m well aware that there may be a gold mine of books on this subject in Japanese awaiting discovery, just out of my grasp. It's a language i'm determined to master someday, just for the purpose of ransacking the book shelves.

I'm afraid I have no credentials to my name except a certificate in the digital arts. I'm interested in writing and drawing my own stories in comic book form. As there's no university for that, I study on my own.

Here are a few anime and manga that I like. Naruto, Full Metal Alchemist. If you ever decide to watch an anime, these two are your best bet. :)

The first two are what I call larger than life plots dealt with on a level that I can identify with. This is a point that I feel fails miserably in movies today. The “Why do I care?” factor. If I can’t be emotionally moved and identify with the journeys of the characters in their stories I simply don’t care. No matter what grand message the movie is trying to get across. The two examples below of mange that I enjoy have me caring deeply because I can understand the frustrations and desires of the characters on a daily life level.

The plot of Naruto is about a boy who is an outcast from birth because he had a demon that was destroying the village sealed into him. People shun him. Because he is an outcast, he has a turning point in the first book where he has a choice to become destructive to the society or be a contributing part of it. The characters he meets mirror that theme on some level. Those other outcasts who chose to actively to use their demons to be a negative impact on their society, those who chose to let others to use their demons to destroy... *sighs* It's difficult to explain. Nartuo is complicated on so many levels theme wise and I can enjoy the story on many different levels: plot, theme, characters, the setting.

The plot of Naruto is about a boy who is an outcast from birth because he had a demon that was destroying the village sealed into him. People shun him. Because he is an outcast, he has a turning point in the first book where he has a choice to become destructive to the society or be a contributing part of it. The characters he meets mirror that theme on some level. Those other outcasts who chose to actively to use their demons to be a negative impact on their society, those who chose to let others to use their demons to destroy... *sighs* It's difficult to explain. Nartuo is complicated on so many levels theme wise and I can enjoy the story on many different levels: plot, theme, characters, the setting.

Fullmetal Alchemist starts on mistake. Two boys lose their mother and study the magic of alchemy intending to bring her back to life. The story theme of this story is quite clear, "to gain something of value, one must lose something of value in return." One boy lost his body in the attempt to bring his mother back, the other brother literally looses and arm and a leg. Their story is a journey to find the philosopher’s stone to regain the brother's lost body. It's interesting because the characters they meet along their journey follow that theme exactly...those who are willing to sacrifice what is precious to them for their goals, and the consequences.

Fullmetal Alchemist starts on mistake. Two boys lose their mother and study the magic of alchemy intending to bring her back to life. The story theme of this story is quite clear, "to gain something of value, one must lose something of value in return." One boy lost his body in the attempt to bring his mother back, the other brother literally looses and arm and a leg. Their story is a journey to find the philosopher’s stone to regain the brother's lost body. It's interesting because the characters they meet along their journey follow that theme exactly...those who are willing to sacrifice what is precious to them for their goals, and the consequences.

Some image links:

Naruto

Full Metal Alcehmist

Signed: Akemi Art

(SW's response in Com Box)

Thank you for your response. I'm very excited to have someone who has studied the subject on hand to ask questions of. Please, lets continue this discussion in your blog. I've always felt that I've lacked something in my story telling, and working exactly what it is out on my own has been a pain.

I feel that I found what I’m missing in my studies and your book clarified it. I am quite frustrated studying anime and manga because I’m well aware that there may be a gold mine of books on this subject in Japanese awaiting discovery, just out of my grasp. It's a language i'm determined to master someday, just for the purpose of ransacking the book shelves.

I'm afraid I have no credentials to my name except a certificate in the digital arts. I'm interested in writing and drawing my own stories in comic book form. As there's no university for that, I study on my own.

Here are a few anime and manga that I like. Naruto, Full Metal Alchemist. If you ever decide to watch an anime, these two are your best bet. :)

The first two are what I call larger than life plots dealt with on a level that I can identify with. This is a point that I feel fails miserably in movies today. The “Why do I care?” factor. If I can’t be emotionally moved and identify with the journeys of the characters in their stories I simply don’t care. No matter what grand message the movie is trying to get across. The two examples below of mange that I enjoy have me caring deeply because I can understand the frustrations and desires of the characters on a daily life level.

The plot of Naruto is about a boy who is an outcast from birth because he had a demon that was destroying the village sealed into him. People shun him. Because he is an outcast, he has a turning point in the first book where he has a choice to become destructive to the society or be a contributing part of it. The characters he meets mirror that theme on some level. Those other outcasts who chose to actively to use their demons to be a negative impact on their society, those who chose to let others to use their demons to destroy... *sighs* It's difficult to explain. Nartuo is complicated on so many levels theme wise and I can enjoy the story on many different levels: plot, theme, characters, the setting.

The plot of Naruto is about a boy who is an outcast from birth because he had a demon that was destroying the village sealed into him. People shun him. Because he is an outcast, he has a turning point in the first book where he has a choice to become destructive to the society or be a contributing part of it. The characters he meets mirror that theme on some level. Those other outcasts who chose to actively to use their demons to be a negative impact on their society, those who chose to let others to use their demons to destroy... *sighs* It's difficult to explain. Nartuo is complicated on so many levels theme wise and I can enjoy the story on many different levels: plot, theme, characters, the setting. Fullmetal Alchemist starts on mistake. Two boys lose their mother and study the magic of alchemy intending to bring her back to life. The story theme of this story is quite clear, "to gain something of value, one must lose something of value in return." One boy lost his body in the attempt to bring his mother back, the other brother literally looses and arm and a leg. Their story is a journey to find the philosopher’s stone to regain the brother's lost body. It's interesting because the characters they meet along their journey follow that theme exactly...those who are willing to sacrifice what is precious to them for their goals, and the consequences.

Fullmetal Alchemist starts on mistake. Two boys lose their mother and study the magic of alchemy intending to bring her back to life. The story theme of this story is quite clear, "to gain something of value, one must lose something of value in return." One boy lost his body in the attempt to bring his mother back, the other brother literally looses and arm and a leg. Their story is a journey to find the philosopher’s stone to regain the brother's lost body. It's interesting because the characters they meet along their journey follow that theme exactly...those who are willing to sacrifice what is precious to them for their goals, and the consequences.Some image links:

Naruto

Full Metal Alcehmist

Signed: Akemi Art

Monday, February 23, 2009

Anime and Manga Themes and Premises

Akemi's Post No. 1

(my comment in the ComBox, below)

I'd like to thank you for writing this book. I bought it awhile ago on amazon, along with only two other books I could fine for figuring out theme and emotions.

I'd like to thank you for writing this book. I bought it awhile ago on amazon, along with only two other books I could fine for figuring out theme and emotions.

I felt that i can write a story (plot wise) but I don't quite have the hang of getting people to care.

Since the books about this subject matter were so sparse, I did and still do a lot of analyzation of theme on my own. This analysis is mostly directed towards Japanese anime and manga.

Underneath all the flash and bright colours most anime and manga have themes and stories that hit me on a gut level. I laugh and cry from one moment to the next. 99% of the movies I try and watch in the theaters don't compell me to have this gut level emotion.

I wrote a piece on character themes on my BLOG "Myth and Manga"... if you are interested in looking at it.

That's actually an interesting question i want to ask you. How do Character themes and Story themes correlate? The anime Naruto I was studying..it doesn't have a story theme. Just individual character themes that focus of acknowledgment of the individual by the society.

Signed: Akemi Art

(my comment in the ComBox, below)

I'd like to thank you for writing this book. I bought it awhile ago on amazon, along with only two other books I could fine for figuring out theme and emotions.

I'd like to thank you for writing this book. I bought it awhile ago on amazon, along with only two other books I could fine for figuring out theme and emotions.I felt that i can write a story (plot wise) but I don't quite have the hang of getting people to care.

Since the books about this subject matter were so sparse, I did and still do a lot of analyzation of theme on my own. This analysis is mostly directed towards Japanese anime and manga.

Underneath all the flash and bright colours most anime and manga have themes and stories that hit me on a gut level. I laugh and cry from one moment to the next. 99% of the movies I try and watch in the theaters don't compell me to have this gut level emotion.

I wrote a piece on character themes on my BLOG "Myth and Manga"... if you are interested in looking at it.

That's actually an interesting question i want to ask you. How do Character themes and Story themes correlate? The anime Naruto I was studying..it doesn't have a story theme. Just individual character themes that focus of acknowledgment of the individual by the society.

Signed: Akemi Art

Thursday, February 5, 2009

More Story Consulting

It's been an interesting month. Without revealing anything, I was asked twice to fly to Utah and hide out in a private snow lodge with actor/producer Will Smith to breakdown stories with the screenwriters, and other consultants. Long 14-hour days, good food, and the wonder of seeing a major motion picture take shape before your eyes on 4x6 index cards. Aside from working with very creative people, it's great to meet others, like those pictured here: Left to right: screenwriters Marianne and Cormac Wibberley (NATIONAL TREASURE), me, and Drew Yanno (also WGA), author of THE 3RD ACT, and film professor at Boston College. On an earlier trip I finally got to know Chris Vogler ("The Writer's Journey") who wrote the foreword to The Moral Premise.

BTW: Taking pictures in the lodge with Will et al was strictly prohibited. I managed to take the picture above of the lodge on our way to the taxi that took us all to the airport. The picture of the four of us was taking on the airport curb. Thanks to photoshop for the rest. Even the sun in both snaps was from the same direction. (Luck)

Thursday, September 4, 2008

Moral Premise Makes It To The Sony Lot

I've been sworn to secrecy, but I can tell you this. Last week I was flown to Los Angeles to screen a major movie in its editing stage (SEVEN POUNDS), have a couple of meetings, and write an analysis of the moral premise. Along with consultants and screenwriters Jim Mercurio (left) and Michael Hauge (right), we watched the film twice over two days on the Sony Pictures Studios lot in Culver City, CA -- once in the editing dens and then in the leather seated Thalberg screening rooms. (That was cool!) And that's all I can say. It was fun, and great to talk to Michael Hauge, whose book I quote several times in my own, after attending one of his screenplay seminars here in Detroit 15 years ago. It is satisfying to know that the audience I targeted The Moral Premise at, is finally discovering it.

I've been sworn to secrecy, but I can tell you this. Last week I was flown to Los Angeles to screen a major movie in its editing stage (SEVEN POUNDS), have a couple of meetings, and write an analysis of the moral premise. Along with consultants and screenwriters Jim Mercurio (left) and Michael Hauge (right), we watched the film twice over two days on the Sony Pictures Studios lot in Culver City, CA -- once in the editing dens and then in the leather seated Thalberg screening rooms. (That was cool!) And that's all I can say. It was fun, and great to talk to Michael Hauge, whose book I quote several times in my own, after attending one of his screenplay seminars here in Detroit 15 years ago. It is satisfying to know that the audience I targeted The Moral Premise at, is finally discovering it.I was sure to wear my MICHIGAN cap on the lot... advertising our state, now with its attractive incentive program, can't hurt. This picture was taken late in the day, but when we arrived early afternoon, the "streets" (at the North end of the Sony lot -- the old MGM studios) were busy with all sorts of folks, including small crews here and there shooting inserts for various projects.

Friday, August 22, 2008

He LIked the Book --- I Guess

HE LIKED THE BOOK... I GUESS

Well, I still haven't talked to him... but my guess is he liked it. A couple of weeks ago Fed Ex showed up at my door here in Michigan with a couple of scripts and a non-disclosure agreement. My wife persuaded me to sign the thing and get to work. Then, after I handed in my analysis, I was invited to make a couple of trips. I guess someone at Overbrook likes the book.

So, I'll be in L.A. next week on moral premise business, and hope to have some time between screenings or afterward to visit with those of you I haven't seen in a couple of years. If you've got some time, drop me an email.

And, no, I haven't written up HANCOCK on this moral premise blog, but I loved the movie. The Moral Premise? Something like Super Indulgence produces a Super Binge, but Super Sacrifice produces a Super Hero...whether fighting crime or raising a family. Moms are super, aren't they?

Monday, July 14, 2008

Hollywood Calls... sort of

|

| Will Smith in I AM LEGEND |

A few months ago I received a call from a lady who said her boss who owned a production company in Los Angeles had read The Moral Premise and wanted her to track me down so he could talk with me. She said she had a hard time finding me because there was another Stanley Williams that kept showing up in her Internet searches. But she figured that the Stanley Williams she was looking for was not on death row in a California prison. It turns out that Stanley TOOKIE Williams III, the gangster, was executed in California a few years back, but Google gives him a lot of "hits."

When she felt it was safe (that I was not in prison) I asked her the name of her boss' company. She said, "Overbrook Entertainment". Now, that sounded familiar, but I don't know my production companies that well, and I felt kind-of dumb, but I had to ask: "So, who's your boss? She said, "Will Smith."

When she felt it was safe (that I was not in prison) I asked her the name of her boss' company. She said, "Overbrook Entertainment". Now, that sounded familiar, but I don't know my production companies that well, and I felt kind-of dumb, but I had to ask: "So, who's your boss? She said, "Will Smith."

Well, I knew who Will Smith was, but I didn't believe it was the same Will Smith this lady was working for... until I scrambled my webrowser and looked up Overbrook. Oh yeah!

When I regained my cool I told her I'd be glad to get a call from Mr. Smith anytime, and to please tell him that I was a fan of his movies.

That night Pam and I rushed out to see I AM LEGEND, just in case he called the next day. That was months ago. No call. LOL! But it was still cool getting Tracy's call and seeing her name in the credits as Mr. Smith's Executive Assistant at the end of I AM LEGEND.

Tracey told me Smith reads "everything he can get his hands on about the business." That probably explains why he keeps making such good decisions. I've been anxious to see HANCOCK for months. If for no other reason, it looks like the first superhero movie that actually respects the laws of Physics.

I'll let you know if Mr. Smith calls. Hope he liked the book.

Saturday, July 12, 2008

Oregon Bloggers Discover Moral Premise

Today (9/4/08, actually) I received this nice email:

Stan

Dr. Williams,Thanks, Ryan. Your two blogs look very interesting. I'm sure to read more.

I recently read your book, The Moral Premise, and enjoyed it greatly! Last year I co-taught a Faith and Film class at Mosaic Church in Portland, Oregon (www.mosaicportland.org) and I taught on the narrative structure of movies and determining the message of movies. Your book was the best resource I consulted. I used the moral premise as a way to help people determine the message, or controlling idea, that the movie intended to convey.

My co-teacher, Martin Baggs, and I led a monthly Faith and Film group for Mosaic Church. For each movie we viewed and discussed, I led the group in looking at the structure and message and framed the message in the terms outlined in your book. People really responded well to articulating the message of the movie in this way.

Martin, my co-teacher, began a blog of movie reviews and referenced your materials.

http://mosaicmovieconnectgroup.blogspot.com

I also started a blog recently focused on the structure and message of stories and referenced your work also.

http://lifeofmystory.blogspot.com/

I posted a blog entry today referencing your book and explaining the moral premise. In my list of recommendations, I included your book, website and blog. I do hope that my referencing your materials encourages people to view the blog and website and hopefully by your book!

Ryan Blue

Gresham, OR

Stan

Tuesday, July 8, 2008

Helen's Lost Arc in THE INCREDIBLES

My Moral Premise pen pal from Greece, Geroge C. wrote me with this very good analysis of Helen's arc in THE INCREDIBLES, thus pointing out a weakness in my book.

George, this is great work. I'm glad you understand the power of the moral premise so well.

Here's Geroge's email, verbatim:

====

Stan, You mention somewhere in your book that in ancient Athens they didn't allow works of art that were damaging to the citizens' moral values. Well, actually that is only a proposal Plato makes in his work regarding how an ideal city should be like, but there wasn't such a law in Athens. And thank goodness, cause, who gets to decide which works of art are good and which ones are bad?! In ancient Greece, the thing which I believe is the most indicative of the close bond between stories and moral premise, is that the origins of theater and the presentation of plays can be found inside religious events. It was within such events that theater and drama was first born. I think that tracing the roots of drama gives us a whole new perspective that doesn't allow us to accept the notion that movies should be simply brain candy.

Thanks for the correction, George. That's important information. (SW)

Stan, I watched the Incredibles and I discovered there's a beautiful character arc (Helen Parr's) that has escaped you! :-) And it's an arc that brings a whole new dimension to the story. You propably don't recall much from the movie right now, but if you ever happen to watch it again, I think you'll agree with me!

Actually, I've lectured on THE INCREDIBLES several times since the book came out, and enjoy showing the clips to groups. As a result, I've seen more clearly Helen's arc, which, as you point out, I did not fully understand when I wrote the book. (SW)In the arc tables of 'The Incredibles', pg 130-133, you say: "The moral premise is that battling adversity alone leads to weakness and defeat, while battling adversity as a family leads to strength and victory." You also cite how Buddy Pine/Syndrome (the baddie) practices a distorted version of the moral premise: He and his partner, Mirage, appear to be working as a family, but in truth Syndrome just uses her and doesn't really appreciate her. When he's given the opportunity to aknowledge the importance of relying on his family, he rejects the idea and shows he's willing to sacrifice Mirage...

Regarding Helen Parr's arc plot (Mr Incredible's wife) you say that "she practices the good side of the moral premise most of the way..." And that's where I have a very different opinion: I think that Helen Parr, just like the villain, starts out by practicing a distorted version of the moral premise's virtue! Helen Parr appears to be the family's bedrock, but what she really does is suppressing the other family members. She doesn't let them be themselves! She strives for a united family, but on her own egoistic terms. And this results in misery and a dysfunctional family. Later, confronted by a moment of grace, she abandons that attitude, embraces the true virtue of the moral premise, and becomes the heart and soul of the family. I've included some story beats which I think prove my point:

We see Helen being called to the principal's office due to her son's problematic behavior at school. When she talks with her son, we find out that Dash's frustrated because she won't let him go out for sports. Dash is naturally competitive and loves sports, but Helen just won't allow it. Dash tells his mom: "You always say, 'Do your best'. But you don't really mean it. Why can't I do the best that I can do?"

Later, at the dinner table, Helen scolds Bob (her husband) for being impressed with their son's superspeed. She says "We're not encouraging this!" Bob himself is very unhappy cause he cannot be Mr Incredible, and it's because of that reason that he has trouble connecting with his family. Even Violet (their daughter) is unhappy; she has an outburst, saying that she's forced to be 'normal' although she isn't. In other words, she's forced to fit a stereotype, and she's not allowed to be real.

Later, when Bob comes home late, he and Helen have a fight. In that scene it's clear that Bob and the kids suffer because they aren't allowed to use their powers. Bob says to Helen, "You want to do something for Dash? Then let him go out for sports." And Helen rants defensively:"I will not be made the enemy here!" She's the one who tries to hold the family together and meet their needs, but she doesn't realize that by trying to make them 'fit in' and by not allowing them to be who they truly are, she sabotages her own goal. In a way, she is the enemy!

Later Helen finds out Bob's been lying to her and that he does superhero work behind her back. She starts crying when she realizes it. She goes to find him and the kids sneak in with her in the jet. There's a big moment of grace here as danger appears, and from that point her attitude becomes very different. She puts on her costume and when things get dangerous she tells her daughter to put a force field around the plane. Violet responds,"You said not to use our powers." Helen says," I know what I said. Listen to what I'm saying now!"

Helen abandons the distorted version of the moral premise's virtue from now on. There are sequences where Helen works with the family and coordinates them so that everyone's power works harmoniously in conjuction with the others. It's fascinating how Helen's character changes; she becomes a true field leader!

Later at the cave, Helen once more encourages the kids to use their powers. She says to her son, "Dash, if anything goes wrong I want you to run as fast as you can." Dash cannot believe his ears. He responds, overjoyed:"As fast as I can?!"

In the movie's final scene when a new supervillain appears, Helen doesn't prevent anyone from using their powers. In fact, she even puts on her mask before Bob does, and gives him an approving look.

Let me know what you think, Stan. Thanks again!

George

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

Why Are Stories Necessary? Part 2

What follows is George Chatzigeorgiou's response (who writes from Greece) to my June 10, 2008 post, which was my (long) answer to his question "Why Are Stories Necessary?"

What follows is George Chatzigeorgiou's response (who writes from Greece) to my June 10, 2008 post, which was my (long) answer to his question "Why Are Stories Necessary?"George's insight into the cultural importance of stories and narrative is inspiring. Yes, he's a kindred soul. But he goes beyond where I've been, and sees things I don't, and that's exciting. His writings, which I'm happy to post below, are like good myths which are retold by following generations, taking the old story and adapting it to the current times and making it again meaningful and infused with truth for the reader. Being from Greece, George speaks, reads, and writes Greek and I suspect he has a classical education -- all of which adds to the discussion.

If you want to read this thread in order, read the Feb. 10 post first, wherein he poses the question and I answer. That link is HERE (Why Are Stories Necessary?) and at the bottom of that post, there's a like to this post so you can read in order.

Herrree's George!

----------------

Hi Stan,

Thank you for giving such an extensive and thorough answer, and for taking the time to explain that process, the whole thing really makes sense to me now.

So, it's through this whole process of simulation, identification, cause and effect, and use of time that good stories can give us not simply wisdom, but the kind of wisdom that only first-hand experience can provide. So the reason a good story is so precious, is cause it basically gives us the opportunity to become wiser without having to pay the price of wisdom, without having to make mistakes again and again until we finally wise up, and without having to invest the tremendous time it takes for us to reach that point. (many lifetimes in my case!)

All this seems to lead me to another conclusion: A boring story, even with a solid moral premise, isn't enough; it won't work nearly as much as a story that is truly engaging. A good story has emotional effect, the proverbial "thrills and chills", and that emotional effect is absolutely essential for this whole process you describe to work. Maybe that's a deeper reason why we're searching for good movies. ('Seen any good movie lately?') Because an emotionally engaging story is much more effective in giving us the "adrenaline rush that sensitives the synapses in our brain to remember the consequence when it occurs." A boring, poor movie, however, simply won't do the job, even if it has a perfectly executed moral premise. Turns out Hitchcock had the right idea when he said, 'A movie should not be a slice of life, it should be a slice of cake.'

Still, all the attempts at creating emotional effect and all the storytelling craft in the world doesn't mean much if a moral premise isn't there to support the story's drama. It just leaves us empty and unsatisfied. I remember when as a teenager me and my brother went to see the 'Matrix'. It was one of the coolest things I'd ever seen, and we were so excited watching those fantastic action scenes, it was unreal how excited I was! But the funny thing is, when I watched the sequels I didn't like them at all, and in fact I was very put off... How strange! The concept was still the same, the story world was the same, the amazing action scenes were even better than the first movie, heck, even the stars were the same! Later, of course, I understood that the only thing missing was the most crucial one: The moral crossroads, the conflict of values which supported the first film's physical conflict wasn't there anymore. Everything was there, everything but the foundation. There was no meaning, no substance. And ultimately, no emotional effect, no 'adrenaline rush'.

The idea that part of the reason movies are so popular is cause they allow us to glimpse our divine destiny and to experience things from the perspective of God, is so simple and obvious, and yet so stunning and mind-blowing! I never thought of such a thing and I still can't say I have fully grasped it, much less its deeper implications (which I suspect are plenty). 'Going to the movies' is so much a part of our pop culture, that one hardly thinks of it as a mystical experience. And yet, that's exactly what it is! When the lights slowly go out and we watch the screen in anticipation, at that moment, right then, you can tell it's not just a feeling of 'let's have a nice time'; it's a deeper feeling, the expectation for something far more profound. And that feeling I've noticed, sometimes it spreads through the room; sometimes it's even as if I can almost touch it. We really do experience divine attributes when we watch a movie. To the five divine attributes you mention I would add one more, the attribute of IDENTIFICATION. Just as in a really good movie we deeply identify with the characters, feel what they're going through and root for them, maybe God also identifies with us (which maybe explains why He's so passionately interested in our salvation)

You write:

It is only in reliving the lives of others (from true history, or metaphor, and parables) that we have hope of that change, BECAUSE IT HAS ALREADY HAPPENED TO OTHERS... in short - PROOF.That's probably why we're so fond of having role models and need people to look up to. It's not just an interest for those people, we essentially aspire to have similar lives with them. That's why in our teenage years we desperately search for idols. What we're really searching for is some hope for our future. It's a way of saying, 'Look, this guy did it'. It is proof that we can change our lives also, and a platform of inspiration. (It just struck me,so weird, that the word "idol" comes from the Greek word "ειδωλον", which means -you won't believe this- "reflection"!

But at the heart of all morality is the INDIVIDUAL and SELF-DETERMINATION... Our choice of our future and our own self-determination is a fundamental truth about the human condition.Curiously, that's a theme that is inherent in the structure of pretty much every story: The hero changing his own fate as well as the fate of other people, of a community, of the galaxy etc, all because he makes a choice and he's gritty enough to stick with it (self-determination). And everything hinges on the protagonist's choice... I've been reading the Proverbs lately, and there's a brilliant verse which I think conveys exactly that: "Guard your heart above all else, for it determines the course of your life."(Proverbs 4:23)

Thanks again Stan, that was extremely helpful!

George Chatzigeorgiou

Tuesday, June 10, 2008

Why Are Stories Necessary? Part 1

I received the following question from my friend George Chatzigeorgiou in Greece, whose excellent input to understanding the moral premise (with respect to the movie MIDNIGHT RUN) I have posted elsewhere on this blog, HERE.

I received the following question from my friend George Chatzigeorgiou in Greece, whose excellent input to understanding the moral premise (with respect to the movie MIDNIGHT RUN) I have posted elsewhere on this blog, HERE.I've bolded certain phrases that George uses, because they are so well put.

George writes:Well, I don't know why I just didn't bold, underline, and highlight the whole message. Didn't I write a whole chapter on this? It seems I did, but I can't find it.

Dear Stan:

I have a question regarding the moral premise which is so basic I'm almost embarrassed to ask it. I suspect the answer must be right under my nose, so please humor me by answering it!

My question is this: We've established that the essence of story is change, or transformation if you like. We've also established that this change of fortune, whether for better or for worse, is dependent upon a moral choice the protagonist makes; and we know that this in turn leads to fundamental truths about the human condition and how best to live our lives, truths which pass on to the audience or the reader, the recipient of the story. It's also widely accepted that stories are not just some luxury of sorts, and that there's a real need for stories that is universal and begins since the dawn of mankind. So, if the ultimate purpose of story comes down to passing on some crucial and fundamental truths, then whey do you need stories to convey those truths? Why do we need the vehicle of a story to do that?

For example, if I say to you, "Battling adversity alone leads to weakness and defeat, while battling adversity as a family leads to strength and victory", why won't my communication have the same profound effect in your life as watching 'The Incredibles'? If this truth is so crucial and so fundamental to the human existence, then why don't we immediately recognize it and abide by it? Why does this truth need to be incorporated in a narrative in order to have a better chance of making an impact on our lives?

Also, do you think a good story with a true moral premise can really change people and make a difference in the world? Is there some sort of mechanism inside us that causes a good story to have such a magical effect? Is there a real logic behind thinking that good stories can really benefit the world and make a difference? Stan, is there a thoroughly convincing logical argument to support that storytellers are really able to make a difference in the world and serve a high purpose, and that they're not mere entertainers who try to convince themselves otherwise?

So, thank you George, for asking the obvious, ubiquitous, elephant-in-the-room question.

George's question get at the heart of what it means to be human. And by human I do not mean "animal," or any other lesser life form. Human beings are different, in the very way George is observing. THEY TRANSCEND everything else in creation. They ask questions like "Why am I here?" "Why is life?" "What am I suppose to do?" and "How can I be good and not bad?" And it is in asking those questions that we touch the very essence of the human condition—we are made in God's image. BANG! We have a self-conscience. Nothing else does. We know there is something more than the moment in time we are experiencing. It is inherent in our being, and we can't escape from it. Those that try to escape end up in psychiatric hospitals. Why story? Why, indeed! Well, here's why.

ONLY THROUGH STORY CAN WE "SEE" OUR LIFE FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF OUR CREATOR. (See link at end.) Our thirst for stories proves the existence of something greater than us, beyond us, looking in on us, giving us meaning, and someone who most likely put us here. The IDEA that we can KNOW what life MEANS, is evidence that a transcendent ANSWER exists.

Okay, okay, okay... forget the grand philosophy and pontificating. Here are some actual answers, which I'll give in antiphonal fashion to George's highlighted comments:

Yes! The essence of life is change and transformation (up or down). We HOPE things, life, situations, ourselves, can CHANGE and get above (transform) our current miserable life. In the Rosary prayer there's this beautiful line — "here in this valley of tears" — which points to our human need to change and be transformed. It is only in reliving the lives of others (from true history, or metaphor, and parables) that we have hope of that change, BECAUSE IT HAS ALREADY HAPPENED TO OTHERS.

If you simply tell me I can change, I don't see it, understand it, or comprehend how the change can occur. But, if you tell me a story or show me the life struggles of someone who has changed, then I BELIEVE, I ENVISION, and I begin to work toward that end. I have a role model, and example, in short — PROOF.

STORIES ARE DEPENDENT ON A MORAL CHOICE JUST AS OUR LIVES ARE

I don't' have time to explain all of this, but hopefully you'll understand that achieving the change we want or need, comes only through our own SELF DETERMINATION. The current political argument about socialism and Marxism vs. democracy and self-determination is what this is all about. God has given us (personally and individually) a choice: make good decisions that are in accordance with the laws that I've put into place which allow the universe to operate smoothly, or buck them and suffer the consequences. (There is a collective decision we can make and suffer consequences, for sure, but the collective is only as good as the mass of individuals who make the decisions. The collective has no consciousness, will, or soul. Only individuals do. And that's why Marxism and Communism and Socialism ultimately fail in all their forms throughout history. )

We are thus not responsible for bad things that happen of which we made no decision that caused the thing to happen. We are inherently (by virtue of God's laws, or natural laws) ONLY RESPONSIBLE FOR OURSELVES and those things that happen DIRECTLY as the result of our decisions. We can yell victim all we want, but ultimately we can control our attitude. If we are maimed by a mad man, our responsibility is our attitude toward the horrific event. Do we become bitter or forgiving? Do we seek revenge or consolation? And yet this does not marginalize or denigrate the importance of corporate decisions or the laws of a republic for the common good. But at the heart of all morality is the INDIVIDUAL and SELF-DETERMINATION -- you take that away and you'll end up like East Berlin during the cold war in very short order.

STORIES TELL US FUNDAMENTAL TRUTHS ABOUT THE HUMAN CONDITION

Our choice of our future and our own self-determination is a fundamental truth about the human condition. God has written into the universe and into all human hearts certain non-negotiable rules. One of those rules is "gravity" by the way. Another is the need to tell the truth if you want to live in community with others. Obey these rules an live. Disobey them and die. (See Genesis 2:17, although we don't need the Bible to know that if we step off a cliff we're doomed to fall to our death.)

STORIES ARE NOT JUST SOME LUXURY OF SORTS

Sooooo right! Stories require time, and time is the critical element of stories that explain life. Stories are as important as time. Only stories can measure and mark time. Stories cannot exist without time. And time is only measured in terms of stories.

One of the things that points to the importance of time as it interplays with a person's life is that rich and poor have the same amount of time. The richest can not can't make more time. They can make more money, but not time. Time is the great equalizer. There is no "class" when it comes to time. Consequently the rich can understand the drama involved in a pauper's life, and the pauper can comprehend the suspense that brings the rich to their knees. Indeed death is a milestone of time and story, and both the rich and poor die.

Time is that ubiquitous "dimension" (although it has no dimension that we can perceive -- it's a zero-dimension, a dot, that moves along a two dimension line called a life's timeline. But we cannot perceived the line, only the dot.

Yet God perceives simultaneously the two or three dimensions of lines that constitutes multiple lives in multiples places at multiple times. And because we are made in the image of God, and because time and story are dependent on each other, stories allow us to look at our lives, and all history as God does. Stories allow us to time-travel, and instantly bi-locate, even tri-locate our minds across centuries and continents. Stories allow us to experience the attributes of God -- the omnipresence, the omniscience, if not also the omnipotence.

SO, WHY DO WE NEED STORIES?

What I just said... to tell time. To tell us IN time, how important decisions are.

Stories manipulate TIME and allow us to see things as God sees them...without the limit of time. We can only experience the Zero-T of time. In reality, we cannot see forward or backward along our timeline or any one else's. But if we tell a story we can move through time and explain why things are, and how they could have been. That is because DECISIONS (especially moral ones) are made in time. A decision is a milestone, a marker, that helps define time. When we decide to study hard and graduate from a school, our GRADUATION DAY marks the culmination of many moral decisions to study so that we may eventually graduate. Thus, graduation is a MARKER of our moral decisions, and the GRADUATION event TELLS us what TIME it is. Telling the story about how we graduated allows us to explore the many moral decisions that we made right so we could graduate, and the many wrong moral decisions a friend made so he would NOT graduate.

Because didactic communication (telling me what to do) does not let me relive the decisions of others and see the consequences of those decisions. If you simply tell me to do something and explain the consequences, the degree to which I believe what you say will happen or not happen depends on a long relationship of trust between us. That trust is the result of many stories and shared experiences passing between us. But if that deep relationship does not exist then there is no realization of the consequence. But a story SIMULATES my life, convinces me that the moral decisions and the consequence have meaning. I can see what happens to Mr. Incredible when he tries to do things alone. I can see what happens to the Incredible Family when they battle adversity together. Because of the relationship with those characters in the first two acts, I IDENTIFY with them. I have established a relationship with them and I am emotionally attached to their decisions. I have lived in their time and their story. I see myself in them because I have made decisions like they have, and to some degree lived the consequences. They reinforce the pattern of my life (assuming their story was created around a true moral premise.)

Unlike didactic communication (telling), narrative communication shows, demonstrates, simulates, and dramatizes the effect of time on those decisions and consequences. Didactic communication has no power to demonstrate, show, or dramatize. You've heard the expression that "experience is the best teacher". Why is that? Because experience creates the drama of time as it relates to decision and consequence, and the suspense between those two nodes. We make a decision (and take an action) and then suspense sets in as we wait to see what the consequence will be. That suspense and intrigue create an adrenaline rush that sensitives the synapses in our brain to remember the consequence when it occurs. Movies especially, but all stories too, rely on this natural method of time, decision, consequence and help us IDENTIFY with the characters as if we were them. Because the story depends on time to work, it can create drama, which gives us an adrenalin rush, which triggers our brain to remember the relationship between a particular decision and its consequence.

Stories also allow us to see inside the mind of a character and know their motivation and moral values, thus identifying the moral good and bad of attitudes and how various kinds of THINKING leads to kinds of ACTION and thus CONSEQUENCE.

A friend used to say to our kids (his daughter and my son before they were married, although it is still true now that they are married with 4 kids of their own): "You can make any decision you want, but you have no choice over the consequence." In family matter that consequence may come from the arbitrary will of a parent. But in society that consequence may come from a policeman, a judge, a jury, or even a spouse. We can cheat on our wife (we have the freedom to make that decision) but we have no control over her jealously or bitterness when she finds out. It's one thing to tell someone "DO NOT COMMIT ADULTERY" but to experience it is a far better teacher. But who wants to go through ADULTERY to learn its consequences? Not anyone, really. So, what's a better way to do it? TELL A STORY. SHOW A STORY. Let people identify with the husband and wife, and learn through a SIMULATION the natural laws of the universe. And, hopefully, they won't do it in real life.

They do, undoubtedly. Newspaper and novel accounts of behavior and its consequence convince far more people than didactic preaching. Movie fans that watch the lives of movie stars come and go, learn a great deal about what not do to if you want to be happy. It's one thing not to get caught with a hooker on Sunset Blvd (e.g. Hugh Grant) but I'm sure Elizabeth Hurley wish he had avoided the hooker altogether. If Hugh didn't learn anything from that story out of his life, we sure should have.

We can easily say that storytellers have value, because people spent billions of dollars each year to watch stories, or listen to them. Stories come in all forms, from the $200 million block buster to the weather report. News, magazines, gossip, parables... they all communicate the cause and effect of moral decisions and their consequences. We can't escape storytellers, because they are as important as time and morality.

ANYTHING ELSE ?

Here's a link to a short essay I wrote years ago (but reposted on this blog) that explains why movies (and stories) give us insight into our "divine destiny." That is, stories help us transcend this life and give it meaning. Transcendence, of course, is the ultimate transformation or change. We hope for a better life. Time empowers that hope. And stories tell us how to achieve it.

Link to Why Are Stories Necessary? Part 2

Monday, June 9, 2008

Stories and Movies - A Window to Our Divine Destiny

(Originally published by CatholicExchange.com April 2, 2002)

Why are good stories and movies so popular?

The last two years (2000-2001) saw movie box office revenues soar. Even in times of tragedy, movies are in style. The events of 9/11 suggested that all businesses, even the film industry, would suffer. Not so. While there was a slump after 9/11, the film business has never been stronger. Why is that?

Seeing What God Sees

Good stories and movies are popular because they give us a vision of our divine destiny. Because we are made in God's image we have a natural curiosity to experience God's attributes. Unlike any other media, movies allow us to see what normally only God sees in five extraordinary ways.