ALIENS IN THE ATTIC (2009) PGI would appreciate your telling me of typos or confusing paragraphs.

A group of kids must protect their vacation home and the world from invading aliens.

Director: John Schultz

Writers: Mark Burton and Adam Goldberg

Producer: Barry Josephson

Budget: $45M

Gross US: $25M

Gross WW: $57M

STARRING

Carter Jenkins (Tom)

Austin Butler (Jake)

Ashley Tisdale (Bethany)

Ashley Boettcher (Hannah)

Doris Roberts (Nana)

Robert Hoffman (Ricky)

Kevin Nealon (Stuart)

A filmmaker friend asked my opinion of Aliens in the Attic (AITA), so Pam and I watched, then I watched it again taking notes and timings.

First Impressions

AITA was an expensive effort at creating a fun family fare...or flick...a sci-fi comedy that no doubt took inspiration from Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Signs, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and a host of alien invasion stories.

I was most amazed at the editing, the shot coverage, the propping and sets.

|

| Bethany and Hanna hid from Dad, but not really |

Thematically, AITA focuses on the importance of family, authority, and teamwork. The film attempted at digs at people who were addicted to computers, game boys, and other electronic devices, but it failed. The father, Stuart Pearson, wanted to re-establish relationships with his children because computers et al got in the way. So he forces them on a family to leave Illinois for a vacation to Michigan (the movie was shot in New Zealand) to get away from all the electronic garbage. But irony gets in the way. It was his children's and nephew's skills at game controllers that saved his family and the world from invading space aliens. (That is not a spoiler.)

Robert Hoffman, Bethany's egocentric boyfriend was goof-ball amazing—a new Jim Carrey, I suppose.

But I was at a loss to find a consistently applied moral premise that kept the story together about one thing.

Why AITA Failed to Connect?

This post goes along with my other critiques of Failed B.O. Movies although it has a lot going for it—budget, interesting characters, good acting (for a comedy), direction, photography, and digital effects and computer animation matched with live action. But here is the short list of failures that audiences require if word of mouth marketing is to succeed:

|

| L-R: Tom, Art, Lee, Hannah, Jake, Bethany |

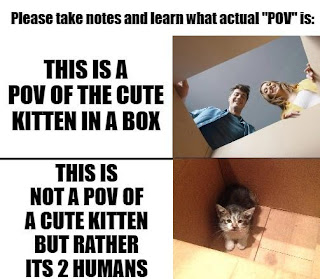

1. There is

no central protagonist or hero with whom the audience can emotionally invest, although the movie begins from Tom's POV and we are told in dialogue that Tom is the team's leader. Rather the group of kids are promoted as multiple protagonists. And yet they don't transform as protagonists should.

2. But Tom's nature is mostly passive. His goal is often distracted, and Jake takes up the cause. In fact, Jake at times tells Tom what to do.

3. We are told through action and dialogue that Tom is somewhat of a genius and a mathlete. Early on Tom hacks his school's computer to change his grades, but Tom does not use his skills at math (i.e. higher intelligence) to defeat the aliens.

4. The actions that prevent the invasion mostly do not originate from Tom (the "brainic,") but come from his proactive cousin Jake, his much younger cousins, twins Art and Lee who master game controllers, his younger sister Hannah who's good at relationships with strangers, and at the very end by the rookie alien (Sparks) who is the one who chases off the invading spaceships. Thus, any emotional investment we make in Tom is diluted by other cast members who often do the heavy lifting and initiate the reversals. The story thirsts for a MacGyver who we can root for.

5. Tom's transformation is sudden at at the very end. From the middle's Moment of Grace we should see Tom struggle with obstructions that slowly transform his attitude, and thus allow him to slowly achieve the goal.

.jpeg) |

| Alien controls Ricky's mind and body |

6.

The goal is a negative goal...

to prevent the aliens from invading the earth. The problem with negative goals is legendary—they are fulfilled at the beginning of the movie, thus movie is over. In the case of AITA, the aliens NEVER invade earth. A positive goal would be to

overturn the alien occupation of earth. With a positive goal the audience can see the progress and cheer at every milestone toward the end. But with a negative goal, the audience cannot cheer at any point for there are no milestones as there are clearly evident with positive goals.

7. The structural staging and turning points are weak (7-14). AITA begins well with a well developed and concise LIFE BEFORE. The INCITING INCIDENT (ideally at 12.5%) is at 17% when the aliens land on the roof of the house and the TV goes "haywire." Shortly there after Tom REJECTS THE JOURNEY to repair the TV dish or defend his siblings or parents from the aliens, whom he meets on the roof. But at 31% into the story, the cross over into Act 2, Tom reasons that the non-adult children (Tom, Jake, Art, Lee, and Hannah) are "the only option, although it is the twins who makes the point that the mind control darts don't work on kids, and it's Jake that concludes: "But we can still fight back."

8. There may be a Moment of Grace. After that, however, there is not clear Moment of Grace for Tom where he has a revealing awareness of what they're battling (a value that changes their efforts) that is different than what they already know. Although as a gang, Hannah discovers at 54% that Sparks is friendly and that changes her attitude, and eventually everyone else's, and it is Sparks that chases of the invasion. This definitely acts as a MOG but not for the POV character, Tom.

9. There is a weak Act 2 Climax (Near Death or Faux Ending). No one actually is physically near death, but after Nana and Ricky fight and destroy the hall, Stu arrives and reprimands Tom and the kids for destroying the house and sends them upstairs. It's that that Tom says, "I'm sorry, guys. It's over...an entire fleet of those guys are about to invade."

.jpeg) |

| Nana Zombie battles with Ricky Zombie |

10. The

Dark Night of the Soul is all too sort as Hannah, Art, Lee (and Bethany, now) encourage Tom to still be their leader. He agrees with a zoom into his face and a music cue, which establishes a

Resurrection Beat. But it's weak because it doesn't come with any NEW revelation that gives them new hope. And it follows with Tom venturing into the basement with Spark's potato gun (not the potato gun that Tom made, but one made by someone smarter, an adolescent alien. No cheers for Tom. )

11. The Final Incident is strong. It's exactly where it should be at 87.5% when the normally small aliens are able to transform into gigantic aliens.

12. Preparations for the Final Battle and the Final Hand to Hand Combat well occupy the last 12.5% of the movie, except the story and action only partially focuses on Tom. Clearly it was the writers' intent to create an ensemble protagonist, which dilutes our emotional connection to a single personality.

13. The Act 3 Climax is anything but a climax although it is perfectly situated at 95%. The spaceship fleet arrives and descends to earth. It is distant and just a collection of pretty white lights. The hand-to-hand combat that we might expect is conducted by these distant lights and Spark's small squeaky voice "Retreat. Retreat. The machine is destroyed. We have been outsmarted by the humans."

14. The Denouement is also perfectly positioned at 97.5% when the adults are clueless about the battle in the backyard and think all the lights in the sky was the meteor shower, and finally Ricky makes a fool of himself at Annie's house, because Tom and Bethany control him from the scrubs. Finally the credits begin with a show reel of Robert Hoffman

15. Deus Ex Machina a la Game Controller. There was a bit of Deus Ex Machina with the kids manipulating people with the game controllers. As opposed to using human ingenuity. Note the game controllers the kids used were from the aliens, not humans. Thus, the story used electronic gadgetry that was, more improbable than possible. Socrates speaks eloquently about how in stories a probable impossibility is better than an improbable possibility. Of course, there's a fine line between those two options. It's up to the writer's craft to show the depth, cleverness and intelligence of the human species. I thought the movie was missing a great deal of human potential, and while funny at times, it’s improbable that electronic gadgetry is going to save the world. It’s more likely that sacrificial human endeavors using gifts, intuition and values that are inbred in the human DNA is going to save the day. So the game controllers end up being the deus ex machina that drops down out of the sky improbably to save the day.

AITA's reference to M. Night Shyamala’s movie Signs and the aliens' weakness in that story of water, was a weak attempt at giving AITA some gravitas. The gravity of water in Signs is the whole idea of "Baptism that saves us" from damnation (1 Peter 3:21)...aliens of a fourth kind. The human element involved in Signs is the Bo's (Abigail Breslin) intuition of putting water glasses around the house because she has a premonition that water is important. [Side Note: the similarity of Bo (Abigail Breslin) in Signs to Hanna (Ashley Boettcher) in AITA, and how Bo discovers the salvation of water, and Hanna discovers the salvation found in her friendship with Sparks.

]

Of course, Signs is clearly a faith story because Rev. Graham Hess (Mel Gibson) is struggling with a loss of faith. The genesis of Hess's character and the water stems from Shyamalanem’s Catholic education as a child, although I am sure he did it unconsciously as few of his other stories make any theological sense. I assert that the simple element of water in a glass (no technology) is more human than a game controller. It might have helped if Tom were to reprogram the game controllers (with his math and technology skills) so that his siblings and cousins could operate them to control the aliens, and putting Tom and his human DNA at the behest of the story’s resolution.

16. No clear oversight of a true and consistently applied Moral Premise. The Moral Premise of a story is a two-sided statement that explains what the story is about at a motivational level. It assumes that all external, physical action is motivated by internal, moral values. That is, the value motivations of the antagonist and protagonist conflict and create the battle. Often the antagonist's values remain the same or turn to a darker vice, but such vices force the protagonist to change values, and seek something better by the end. In AITA the aliens do not change, except for Spark, but the persistence of the humans, and transformation of Sparks (to see the humans as nice), saves the family and the planet. Thus, Sparks transforms, as does Hannah and the others toward Sparks. But there is no transformation of Tom which aids him (or the others) in defeating the aliens.

.jpeg) |

Jake and Tom consider their options

with the potato gun. |

Oft times in stories, it's the vice the protagonist embraces at the very beginning of the story, that opens the door for the antagonist to attack at the Inciting Incident. There's no clear indication that the aliens come as a result of Tom's lame attitude about the vacation. Although, a slightly different script might have portrayed the aliens as a personification of Tom's "lame" attitude, and thus the aliens became a metaphor for changing Tom's attitude. That is the epitome of a vice can repulse a protagonist form the vice toward a more virtuous attitude. But that is not what happens in AITA.

Instead, the need for the audience to see Tom's redemption ends up as...

17. Gaslighting the Audience

Another way of looking for the Moral Premise is to ask more specifically, "What could be the virtue and vice conflict in AITA?" and how might they be articulated in a moral premise statement? Or, what transformation is evident in the characters from vice to virtue? There are transformations.

At the very end Tom tells his father, Stuart, that Father Knows Best ("Dad, let me save you the lecture. You were right and I as wrong," and Tom decides to enjoy fishing with the family. But there is no slow, observable, learning or transformation. Tom's change is sudden with the fixing of the tangled fishing reel (a repeated metaphor motif of the family's situation).

And there's no logical connection between his father's desire to get Tom away from technology, when in fact it was technology that saved the family and the world. So Stu could not have been right. Stu was in fact wrong. It was the kids' knowledge of technology (and game controllers) that saved the family. By telling Stu he was right, Tom sanitizes the plot, lies to the audience, and patronizes the "family" movie critics.

Subliminally, audiences are not gullible enough to such a gas pipe (gas lighting, as Jakes makes such the passing reference about Ricky "What a gas pipe.")

Thus, Tom's sudden transformation at the end rings hollow, and audiences "feel" a cognitive dissonance. It's just not true. Based on the story alone, not reality or natural law, Dad was wrong about technology, Ricky, fixing Ricky's car, the relationship between Ricky and Bethany, the thermostat, and Tom's guilt at wrecking the hallway. There are times was Stuart and his wife Nina were very aware of what the kids were up to, and were right, but they were ever clueless about the aliens and the battle for what was right.

Based on the first few minutes of the movie, the Moral Premise could have been:

Human technology destroys family relationships; but sanitized human interaction heals relationships.

But that is not what the movie proves. Instead AITA suggests the truth (a false truth) is this:

Human technology destroys family relationships; but alien technology saves it

...or something like that.

Another theme that might resonate as false with the audience is:

Advanced technology can save the world; but gaslighting can save the family.

You see, at the end, Tom has become like Ricky...the bad boy. Tom is gaslighting his Dad, patronizing Stuart, telling him that Father knows best, when the audience knows just the opposite it true. But the attitude, tone, lighting, music, all other aspects of the Father-Son talk on the steps, give evidence that the filmmakers are gaslighting the audience by sanitizing the ending, and telling a lie.

That's just another reason why AITA failed at the BO.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)