|

| (found on the web) |

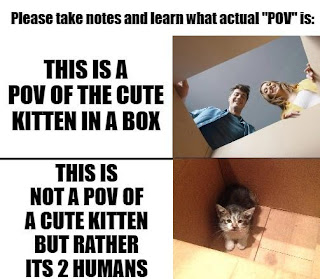

Unfortunately, I continue to see published writing that ignores or incorrectly uses POV. Such misuse leads to cognitive dissonance (which takes the reader out of the story long enough to figure out what the writer intended).

Properly used POV creates a "suture" between the audience and the characters. In medical practice a suture is the stitching together of an open wound that allows separated flesh to fuse and grow back together, hopefully without a scar. "Suture" therefore, is a good metaphor for the use of POV in narratives as the writer stitches the reader emotionally into the story without leaving a scar.

IN SCREENWRITING a proper POV technique requires three shots.

Shots 1 & 3 visually communicate the character's emotion (the effect), which is explained by shot 2 (the cause).1. A closeup of the POV character who looks, stares, or glares off screen in wonder, disgust or shock. (CUT TO)

2. What the POV character sees from their perspective, as the character's eyes are replaced by the camera's lens. (CUT TO)

3. Return to the POV character who emotionally and physically reacts to what is seen.

You've seen this sequence is every film you've watched. BUT what is often missed in the scripts I see is how the writer portrays the sequence. Too often a script will skips shots 1 & for the sake of supposed efficiency, e.g. "Doug sees Mary wink at Jake and becomes jealous." Doing this robs the reader of emotional connection with Doug and his wonder, disgust, or shock. It also confuses the reader as to who is jealous, Doug, Mary or Jake?

IN PROSE (e.g. novel) establishing the POV character is a bit more involved, but the same three "shots" or lines of text, are necessary if we are to connect with the intended character. For example, in the following three paragraphs everything is experienced from Peter's perspective (i.e. POV):

1. Peter, hearing Melody's scream, entered the kitchen and was greeted by his irate wife and a pile of chaos on the floor. His heart fell and his knees shook.

2. Stacey, their three-year old daughter sat on the floor in a pool of chocolate syrup she had squeezed from a bottle she held upside down, high over her head. Her blonde hair, face, and romper drooled with the sweet goo. She smiled with pleasure.

3. Peter took a deep breath and stepped carefully backwards, his flailing hands groping for the door handle to the wet mop closet.

Note: We use 3 paragraphs because each paragraph directs our attention to a different subject in a location different than the one before. Putting these in one paragraph suggests our view is in the same direction for each. But our view changes, thus three paragraphs works better than one, and the white space breaks up the page for easier reading. (Do I follow this rule? Ah...well...not when I'm trying to cut down on the page count.)

Often, however, what I see in prose is this, in one paragraph:

"Come see this mess. Right now!" Stacey, very pleased with herself, was on the kitchen floor in a pool of chocolate syrup. It tasted sweet and yummy. Very disappointed he shook in anger and grabbed a mop.

Now this paragraph is much more efficient. But it involves three points of view and not a little confusion:

"Peter! Come see this mess. Right now!" is someone's POV but we're not sure who. In context we can assume it's Melody, Peter's wife, if Melody was in the kitchen moments before.

Stacey, feeling pleased with herself... it tasted sweet and yummy..." is Stacey's POV. It's telling us what's inside Stacey's head.

Very disappointed, he shook in anger and grabbed a mop...is Peter's POV or Universal POV.

This causes the reader, in one short paragraph, to jump between three perspectives and thus dilutes any emotional empathy the reader might have for any one of the three.

Jumping POVs can also happen across three paragraphs. For example here is an abbreviated and edited cold opening for a book I was recently asked to review:

I will never forget when the father and his young son arrived at the clinic. Both were battered and bloody. The boy's eyes were swollen nearly shut and he had a chest wound from which fluid pumped with every breath he took.

Nearly dead, Muhammed looked up at the strange medic sticking a tube into his chest. He feared for his life because the medic was white and he had been taught that white people hated him and wanted to kill the children in his tribe.

When not wearing scrubs the medic was a soldier in the U.S. Army who had been warned to avoid contact with the locals.

These abbreviated paragraphs force the reader to disconnect and jump emotionally from the medic's POV, to Muhammed's POV, to a universal POV. Each jump dilutes if not disconnects emotional involvement with the characters, and lessens the impact of the story.

It would be better to write those three paragraphs from one POV and build up the emotional connection.

I will never forget when the father and his young son arrived at the clinic. Both were battered and bloody. The boy was nearly dead. He had a chest wound from which fluid pumped with every breath he took. As I inserted the chest tube into the boy's wound and began pumping fluid from his pleural cavity, he looked up at me from swollen eyes with fear and not a little trembling. I had heard that his tribe had been taught that white people, like me, wanted to kill their children. How sad. I wanted so badly to keep this child and his father alive. What would he think, I wondered, if he discovered I was a soldier in the U.S. Army?

"...From the very beginning the characters sprung to life. I laughed, celebrated and mourned with the characters. I was there with them, and I cried..." —Kathy M.

"...The character development is excellent..." — Betty S.

"...wonderful character development and page turning plot..." — Hope S.

"...skillful portrayals of the cast of characters whom he brings to life - and for some - to death..." Mike M.

You get the point. POV works, but it takes some work.

No comments:

Post a Comment