Discussion and analysis of screenplays, scripts, and story structure for filmmakers and novelists, based on the blogger's book: "THE MORAL PREMISE: Harnessing Virtue and Vice for Box Office Success".

Friday, December 5, 2025

Pomegranate the Movie Scores Big

Thursday, November 13, 2025

SABRIYA Writing Journal 10 - MORE (Take 2) Capturing and Engaging Your Audience

In keeping with the previous post on Writing to Capture and Engage Your Audience (Writing Journal 9), this post highlights storytelling techniques based on the action-thriller genre, using the 2008 thriller Taken as the model.

You will need to be familiar with the movie to make sense of the explanations below, although hopefully, the subtitles will make sense on their own. To familiarize yourself with the story and structure of TAKEN, visit my original TAKEN Beat Analysis post.

AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT TECHNIQUES

Act 1: OrphanAct 2A: WandererAct 2B: WarriorAct 3: Martyr

Monday, November 10, 2025

SABRIYA Writing Journal 9 - Capturing and Engaging Your Reader

In September and October (2025), I made several presentations to writing conferences in Florida, West Virginia, Michigan and on-line on How to Capture and Engage your Audience (or Readers). There were seven basic methods I outlined in the presentation. You can view and download the PDF of that talk HERE.

Staying within that theme, below are 22 more ideas from my analysis of Thomas Hardy's Far From the Madding Crowd, which I have just finished, although I am far from finished with it.

While Madding Crowd was enjoyable for me, I suspect it was for reasons that differed from other's. For me, it was research that involved a lot of highlighting and note-taking. I wanted to be a better writer, and over the last six months, in preparation to dig into the Sabriya manuscript, Madding Crowd ended up being the most noteworthy of the six novels I read. Below, I share what I have learned, or been reminded of, from Madding Crowd.

I had purchased and extensively highlighted the Penguin Classics paperback edition (first published 2000, reprinted 2003) of Madding Crowd. The novel was so popular, even in Hardy's day, that it was released in various volumes and series, and revised by Hardy (in 1895, and 1901) and others, and found readers not only in England, but the U.S. My copy includes an editor's preface, a chronology of Hardy's life, biographical notes, an introduction, and many, many footnotes comparing various editions to one another and explaining references to Biblical and other classical texts that Hardy mentions in the story. There is also a glossary so modern readers can better connect with the culture of Wessex, England in the late 19th century.

Because of my fascination with the history of Western Civilization, I suppose, the book had extra appeal. But as a writer, setting off on his 4th novel, and 9th book, after hundreds of documentary films and videos and as many screenplays on which I've consulted or written, I knew I still had much to learn.

Yet, I am still haunted, even amidst the notes below. Sabriya is supposed to be a contemporary action-thriller, and Madding Crowd is a historical romance. Thus, what I think I may have learned may not be learning enough, or learning in the wrong direction.

Nonetheless:

- BE THE OMNISCIENT WRITER: Write as the omniscient writer (not omniscient God). "Little did he know that..." and "Bathsheba, however, had other ideas..."

- CHARACTER POV. Stick to a single character's POV in a scene, with occasional flourishes as the omniscient writer, perhaps at the end of the scene. Hardy doesn't do this, and when he shifts POV, it always takes me out of the story to get into another character's head.

- USE SCENE-SEQUENCE. Write paragraphs in the Scene-Sequel paradigm to employ an emotional-rational roller coaster at the paragraph level.

- SCENE DESCRIPTIONS. Start scenes with a detailed description of the setting, including weather, harvest, animals, landscape, season, birds, prey, and flowers in such a way as to parallel the coming action, attitudes, or foreshadow the tragedy afoot.

- PLOT AHEAD-OF-TIME PLOT REVERSALS. Plot regular hard reversals of the plot (turning points). Do not neglect (that is, consider using) asymmetrical reversals within the protagonist or antagonist's mind apart from the physical plot. That is, a reversal that does not need to be physical, it can be only psychological. E.g. "...considering the rum creatures we women are." (Liddy to Bathsheba) ["Rum" in the feminine old British context means "strange" or "odd."]

- APHORISM FACTORY: Aphorisms are Hardy's superpower. Try for at least one aphorism per page (omniscient writer POV), a pithy saying of truth that reverses the use of nouns and verbs. E.g. "The passion now startled him less even when it tortured him more." and "We learn that it is not the rays which bodies absorb, but those which they reject, that give them the colours they are known by." And, "He was drenched, weary, and sad, but not so sad as drenched and weary, for he was cheered by a sense of success in a good cause." (Oak after covering the ricks before a wind storm.)

- WRITE IRONIC: ...descriptions of all characters (make them round, not flat), e.g. "Her emblazoned fault was to be too pronounced in her objections, and not sufficiently overt in her likings." [Actually, that's an aphorism; the irony comes in the detail of what that aphorism summarizes.

- UNREQUITED ROMANCES: Build in multiple fierce but unrequited romances (love triangles or quadrangles). One may be noble and true (Oak), one persistent and mad (Boldwood), one manipulative and lustful (Troy).

- HOUSE OF CARDS: The relationships between key characters must be interdependent like a house of cards. This creates tension; if one fails to create suspense, the others fail to be necessary. (hey, that's an aphorism.)

- REASON WITH GAPS: Make speeches and character motivations rational, but also (omnisciently) point out gaps in reasoning.

- WOMAN'S INDECISION: Much of Hardy's drama in Madding Crowd centers on a woman's indecision (due to a sense of misplaced and exaggerated obligation or guilt) and a man's deceitfulness (due to achieving the goal at all costs, even to oneself). This creates massive psychological upheaval of values and thus poor decisions and actions that result in natural consequences.) Bathsheba to Liddy: "I feel wretched at one time, and buoyant at another." Women (typically or in general) tend to be global thinkers, and are affected by their significant monthly hormonal cycle. This "indecision" (due to conflicting priorities) is one reason why romance novels, with women as protagonists, are best sellers, and where the plot can be summarized as "I don't know what to do." Women buy such novels because they easily identify with the characters and their predicaments.

- LET NATURE REVERSE: Don't neglect reversals induced by nature (Fire, Floods, Storms, Earthquakes). Always foreshadow such reversals and describe how nature (animal instincts) predicts them. Such are never elements of "deus ex machina." Such can be handled as secrets that only nature knows, e.g. foreshadowed by the omniscient writer. As in all turning points and reversals, draw them out, detail, chronology, give them an inevitability, never let the reader imagine the reversal "just happened." (e.g., the long queue of the windstorm and thatching of the wheat and barley ricks.

- TAKE TIME TO REVERSE. Never describe a turning point quickly. Dwell on the detail, stretch it out, make it essential. One of my favorites is in Tom Clancy's Clear and Present Danger , when a smart bomb is dropped on a drug cartel meeting in Colombia. Clancy takes pages to describe the setup and the seconds it takes for the bomb to be targeted, launched, armed, dropped, and explode.

- NATURE'S OMNISCIENCE: Let Nature describe God's or Satan's (the supernatural) attitude about the scene. e.g. Fanny's grave, (ennobled by Troy as an act of penance) is destroyed by rainwater from a gargoyle's mouth.

- INTEGRITY RISES FROM ASHES: In the midst of moral failure, let integrity arise, although too little too late. e.g. Bathsheba honors Fanny's grave, Boldwood negotiates with Troy for Troy to marry Bathsheba, Bathsheba runs after Oak after dismissing him (multiple times), Boldwood turns himself into the gaol (jail), Oak marries Bathsheba on the last page...but why not even a kiss?)

- INDEFINITE NOUNS: Use omniscient observer pronouns as a unique reference with different emotional connotations: E.g. in reference to Fanny: dead fellow creature, our sister, member of the flock of Christ, unconscious truant, the body.

- DELAYED REVEAL: Before revealing the pivotal action, exhaust the inner monologue of dilemma with all possible actions and consequences and leave doubt about what the character will do. Reference the Scene-Sequence model. Consider if it requires a flash forward.

- GAP FILLING: Make the audience work. Try not to reveal a key element of the action, but describe around it. E.g. We never read how Bathsheba opens up Fanny's casket. We read that Bathsheba was determined to look inside, we read she searched for a tool, we read what she saw (although it was censored in one edition), but we never read how she pried open the box. This forces the reader to be intellectually engaged.

- ACTIONS NEED NOT BE ONE OR DECISIVE: ...but two or several and not decisive. In this technique, the earlier actions decided upon are abdicated in the process of taking the action (for reasons announced) until falling upon the final action taken. E.g., Bathsheba decides to go down one road, but retreats, and then goes down a second path, but retreats, and finally goes down a third.

- FLASH FORWARDS: This is partially covered above. The Flash Forward without preamble can confuse the reader, for it will appear (should appear) out of order. But a subsequent paragraph can explain why. That is, present the action first (when dramatically appropriate) and then FLASHBACK to explain in detail, even recounting the inner monologue that brought the action to fruition. However, there should be an emphatic surprise at the end of the Flashback to reward the reader for retreating in time.

- INDIRECT LANGUAGE: This is like subtext, although subtext is usually found in dialogue. Indirect is a technique that mimics real dialogue or description by avoiding the explicit and describing, instead, the emotion, the attitude, or the mood. This can be done with an explicit description of nature or the setting. E.g. a sad situation in a setting of fog and dampness...when Bathsheba discovers her husband, Troy's, infidelity, she is lost emotionally and retreats overnight to a swampy area. Liddy comes to console her, and Hardy describes Liddy's steps across a bog that Bathsheba believes will swallow Liddy up. Although Liddy's feet sink into the spongy bog, it supports her, and she reaches Bathsheba. The blog here perfectly resembles Bathsheba's doubts about her life and refusal to take the steps to recovery.

- NAMES MUST SHOULD SOMETHING. Gabriel Oak is like an oak tree and an archangel. His integrity, strength, and truth are always intact. Bathsheba Everdene is forever beautiful and tempting like King David's Bathsheba who is worth stealing and dying for. Sgt. Francis (Frank) Troy is a Trojan Horse who is frank to a fault, militantly clever, and manipulative. Farmer William Boldwood, is the "strong-willed warrior" (William) who is bold and persistent to a fault, and mad. Fanny Robin is free as a bird. Fanny is also a vulgar, old British slang for a loose woman, which Fanny becomes.

Tuesday, November 4, 2025

SABRIYA Writing Journal 8 - The Real Drama is Mostly Invisible ... VALUES and Inner Monologues

|

| Plot Beat Board for Sabriya Novel. Writing has begun. Planned: 37 chapters, 72K words |

|

| At right, is Thomas Hardy's "Far From the Madding Crowd." |

I am not capable of mimicking Thomas Hardy in Madding Crowd. But I can't help but idolize passages like the following:

Boldwood was thus either hot or cold. If an emotion possessed him at all, it ruled him: a feeling not mastering him was entirely latent. Stagnant or rapid it was never slow. He was always hit mortally, or he was missed. The shallows in the characters of ordinary men were sterile strands in his, but his depths were so profound as to be practically bottomless. (Some of these delicious words were omitted in the 1912 edition as noted in the footnotes of the Penguin Classic edition shown above.) [Chapter XVII, p.105]

FRTMC (2015) Carey Mulligan (Bathsheba Everdene)

and Michael Sheen (William Boldwood)

Multiple movie efforts. We've seen the 1967 and 2015

versions (our favorite).

The above paragraph is a (physical) plot-worthy necessity as it foreshadows Boldwood's actions that bring the novel to a bold and surprising climax (not herein spoiled). The paragraph also foreshadows Bathsheba's internal reaction that unfolds in a subsequent paragraph. Together, the two make the climactic ending sensible and complete.

Yes, novels can do much more than movies when it comes to revealing the truth of a story, and not overemphasizing the metaphors.Bathsheba was far from dreaming that the dark and silent shape upon which she had so carelessly thrown a seed was a hotbed of tropic intensity. Had she known Boldwood's moods her blame would have been fearful, and the stain upon her heart ineradicable. Moreover had she known her present power for good and evil over this man she would have trembled at her responsibility. Luckily for her present, unluckily for her future tranquility, her understanding had not yet told her what Boldwood was. Nobody knew entirely: for though it was possible to form guesses concerning his emotional capabilities from old flood-marks faintly visible, he had never been seen at the high tides which caused them. (Chapter XVII, p.106]

Sabriya, an action thriller, unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on your tolerance for internal dialogue), will be more pulp fiction novel than classic.

Friday, October 24, 2025

Adam Livingston Descendants Join Wizard Clip Book Signings

|

| Jeff Livingston and Stan Williams |

For years, Jeff and several in his cousins, uncles, and brothers have researched their linage, and discovered their relationship to Adam Livingston of the Wizard Clip events, and in past years have visited Priest Field where there stands a shrine to Adam. Jeff found my historical novel, Wizard Clip Haunting, on Amazon, bought a copy, and then contacted me. I was thrilled to get his email, and I sent him a signed copy of WCH, which he told me later he stored away for safe keeping. Jeff finished the long novel before flying to WV to meet up with me.

The picture at right is the two of us before heading into Martinsburg, WV's FIREBOX BBQ for dinner on Oct 8, 2025. Jeff had decided to fly up from Texas and join me for several events leading up to the annual Middleway Day street fair on Oct 11 where I would be giving away and signing copies of Wizard Clip Haunting as well as Eve's Story, the YA adaptation.

The next day Jeff joined me for one of my radio appearances on WRNR with Rob Mario and company, and then that night his cousin, Joel Livingston joined us for a book signing at the historic Martinsburg train station, which today doubles as the For the Kids by George, Children's Museum, directed by Aubry Ervin, assisted by a board of directors which includes an early fan of WCH who has become a close friend, Donald Patthoff, DDS. We were given a grand tour of the historic train round house and then a few people showed up for a talk in the station and book signing my yours truly and the Livingston cousins.

|

| Jeff Livingston takes in the expanse of the historical Martinsburg railroad roundhouse. |

|

| (L) Adam Livingston's Shrine and 8th generation grandsons. (R) Guiney, Susan Kersey, Joel & Jeff Livingston |

On Saturday the weather was perfect fall day on East Street along the Middleway cemetery for the annual Middleway Day Fair. The turn out was huge, and I was out of WCH books (both editions) in just two hours. Jeff and Joel claim they sustained writers' cramp signing over 150 books. Middleway historian Larry Myers, who lives in Middleway and who I interviewed during my original research years ago, and whose ancestors owned property across the street from the Livingstons, paid our booth a visit and continued to share historical insights.

|

| (L) Jeffrey Livingston, and (R) Joel Livingston at Priest Field October 10, 2025. |

I encountered a typical novelist's problem of accounting for eight children and following up their stories, and escalating their subplots plots without diluting the main trust of the Wizard Clip and the family's encounter with Catholic priests. Early on I decided to create an entertaining story that was close to history, and thus I decided NOT to write a history that might be dull. Thus, I compacted the eight children into four, Eve, Henry, Martha and George.

- George (1764–1834)

- Agnes (1767–?)

- Henry (1762–?)

- Eve (1769–?)

- Sharlotte (1770–1837)

- Mary Ann (1772–?

- Jacob (1773–1854)

- Catron (?–?)

Tuesday, October 14, 2025

WARNING: Wizard Clip Jr is Dangerous for YA Readers

|

| Only 8% the length of the full-length novel. Available in paperback and ebook editions. |

A Virginian mother who is also a grandmother and author of a YA book or two, was given a copy of Wizard Clip Haunting Jr.—Eve's Story. She didn't like it. She sent me a long and varied critique. She said she would never let her children read it, but perhaps she meant her grandchildren. She feared that readers would copy the behaviors of the priest characters, and that my fictional accounting of the events was not historically accurate.

Therefore, I want to warn the 80 recipients who received a copy of Eve's Story over the past two weeks during my speaking and book-signing tour. Evidently, this YA book is dangerous. Perhaps you should not read it or let children read it. But I'm not giving refunds. Details below.

Of course, these concerns are present (even more so) in the full-length novel. So be careful out there. If you have the same concerns, or not, please comment.

WARNING LABEL - Eve's Story

- Sure, it's a historical novel, but it's historically inaccurate.

- Some behaviors of the Catholic priests are "entirely un-Christian."

- Adam Livingston's daughter, Eve, prays to her deceased mother for intercessory help. Christians are forbidden to pray to the dead for help, even if they're in heaven.

- A faithless Lutheran minister's behavior is exaggerated and in poor taste.

- Adam Livingston engages in a physical battle to the death with a demon. Christians should never do this.

- The descriptions are far too graphic for young readers, as are the Goosebump books.

- A priest would never sin by giving communion to a non-Catholic, even though Pope John Paul II did it several times.

- The portrayal of Adam Livingston's frailties will offend living descendants, although one 8th-generation grandson said he "loved it."

- Baptisms should be in the church and would never have occurred in a river.

- The evil in the story is pervasive and too strong.

- There is much more to dislike since the author's imagination was unnecessary...

Thursday, August 14, 2025

SABRIYA Writing Journal 7 - Laughter, Reading, & Distractions

The laughter comes from my ever-changing mind about the working title of this book I hope to write. I got tired of trying to pronounce "Shenzhen," although it should be easy, and I like alliterations. Besides, Hong Kong is next door to Shenzhen, and yet I need a visually interesting but fictional place to avoid geographical faux pas descriptions. So, for the time being, the story takes place in and around Hong Chi's environs.

READING RESEARCH

One of the tasks I undertake before getting too far into creating a manuscript is to read inspiring literature, hopefully in the genre that I intend to write. But, in this case, I'm a novel behind. Right now, the book I'm enjoying and marking up is something I should have read before the novel I just finished, Tiger's Hope (see below the distraction). Tiger's Hope is a cautionary tale about a singer-songwriter's IVF mix-up, a few Catholic priests, and a prelate. SABRIYA, while there is a subtle Catholic motif to the story, is NOT about the church or its prelates.

|

| Shenzhen and Hong Kong at Night by Mike Leung (flickr) |

Regardless, the idea is to read an author that I want to emulate. I hope to learn how to write better. I stumbled upon the prolific pile of 105 books written by Ralph McInerny (1929-2010), 52 of which were fiction. A little research suggested that "The Priest" (1873 ~160,000 words) may have been his best. I'm only 102 pages into the 563, and so far, there's plenty to admire in McInerny's command of English. The Priest is about a young man who has just returned to Ohio to be a junior associate priest after three years in Rome earning his Doctorate of Sacred Theology degree. The conflicts he faces are rooted in the shadows of the Vatican II council, a controversy that persists today despite the council's sessions, held long ago between 1962 and 1965.

Nonetheless, here are some juicy examples of language...pardon the lack of context. Similes, metaphors, color, and ironic juxtapositions.

"Trying sinning on the side of charity, Monsignor."

Arthur Rupp was a first drip followed by many more...

...his brows dancing suggestively...

"Someone's been taking notes on your forehead."

Something happened to the embalmed line of Agnes's mouth, as if she were trying to pop the stitches and scream that she was still alive.

She turned abruptly, the movement causing her eyes to snap open. She might have been catching him in a lie.

Did he really think Rome [the Vatican] was the buzzing center of it all . . . its major industry was postage stamps.

A moral theologian had several dozen ways of being less than candid [i.e. lying]

His voice seemed to force its way through the bridge of his nose.

...the newer neighborhoods and eventually suburbs spread west, munching into the orchards as they go...

...eyes downcast, corners of the mouth drooping, a general promise of tears.

"...the Second Vatican Council is a vicious rumor launched by Newsweek and the National Catholic Reporter."

The row of brick residence halls might have been a squadron of sinking ships.

She peered at her watch, hidden in a fold of flesh.

She wrinkled her nose and knitted her brows, prepared for the worst.

She became a poet of the nuptial bed in public.

It (the confessional) was a setting for the enactment of sad scenes.

Bev freed a pickle slice that had been embedded like a fossil in the hamburger bun.

...but no matter where he looked he saw the infinitely interesting landscape of himself.

He had bared his soul to her, such as it was, and now they were to cuddle and coo. She felt like throwing up."

The Priest is a great read. I'm reading scenes aloud to Pam, as she doubles over in laughter .... hopefully at McInerny's wit and not my reading.

And now for the... |

| Rejected cover (left) Desired cover (right) |

Thursday, July 24, 2025

SABRIYA Writing Journal 6: Grammarly

Over the past week, I've been forced to take a break from Sabriya of Shenzhen to make progress on another novel... the one before Sabriya—Tiger's Hope.

I've titled this post 'Sabriya...', however, and not 'Tiger', to illustrate an essential aspect of a writer's life—life is full of interruptions and is really only a stepping stone for the current project.

That means the diversion to work on Tiger's Hope must and inevitably will advance Sabriya's progress.

How did that work out for me?

Tiger's Hope is a 57,000-word novel based on a screenplay we almost produced a decade ago. I've blogged about this earlier. After finishing the draft and reading it aloud to ensure the structure and plot flowed smoothly, I was ready to have it proofread.

My regular proofreader was free (my sister, the editor), but I've overworked her, she's busy this summer, and this novel didn't interest her that much. I had no problem with that.

I've been fortunate to work with a half-dozen proofreaders over the years. None of them were perfect. Even with my bad grammar skills, I was still finding things they missed. I was worried that since G missed the error, it might miss even more, and I would never find what was missed. On Wizard Clip Haunting, there were four editors, and each one saw more and more things wrong. It was disheartening.

Okay, so let's hire a "professional."

Proofreaders for a 57,000-word novel cost from 0.7 to 1.5 cents per word, or $400 to $855. That's reasonable. I queried the $400 proofer. She was not taking on any more work...which translates to, "I've underpriced my services."

Next, a $650 proofreader might have been able to review my novel in about three months. I was not willing to wait that long.

All this time, I was thinking about how I needed a foolproof way to look at every comma, every sentence with cold, calculated eyes... when the word algorithm came to mind. That meant computer, and that suggested A.I.

I'm not in favor of AI-generated text. When an author uses it to generate text, it's not the writer, and it makes sense that what I've read is true—a writer who uses AI to write can't remember what "he" wrote. So, what good is it to him? That probably reveals that I'm not very well off financially. My goal is not to make money, but to learn and instruct, so that I can know even more. I'm repulsed by all the "get rich quick" memes on social media about having an AI generator write a book and the "writer" collecting the royalties. Sorry, I find that repulsive and right up there with fake news.

However, I have no problem with a computer pointing out that I've misspelled a word or that my grammar could be improved.

After a day of researching AI proofing tools, although not in-depth, I chose Grammarly. As I suspected, it wasn't perfect and over the entire book (I finished Grammarly's proofing of the 57,177 words last night), I manually rejected about 50% of its "corrections." So, here's a review of my findings. And to cut to the chase, I believe the novel is significantly improved after using Grammarly than it was before.

SETUP NOTES and CONTROLS

MY COMPUTER

I work with Microsoft Word at this stage (after I draft in Scrivener). I am working on a 2015 Power Mac (tower) running macOS Monterey (12.7.6). I have two 27" displays. While I'm surrounded by RAID 1, 2T–16T external ThunderPort drives, my manuscript writing is done on the system's 1T Solid-State Memory. I've discovered that MS Word does not like to save files to an external drive without creating a temporary file to work on. After an hour's work, I realize I've been typing into a Word Temporary file with an incomprehensible file name that can't be found without using 'Save As'...

GRAMMARLY (G)

I installed G-Pro ($12/month) on my Mac, including Grammarly for Mac and Grammarly for Word. There is also a web browser version, but it does not allow me to preserve my Word Styles and other formatting. On my computer, two versions may conflict, and G's Support team keeps advising me to turn one off or uninstall it due to issues that arise. I tried that once, but rejected it for the reasons cited below.

There are actually three G controls on my desktop:

(1) In the Mac Tab bar at the very top of my primary screen. It's a pull-down menu that allows me to turn G on or off for different applications. Currently, it is off. When it's on, it's like a grammar teacher constantly looking over your shoulder and telling you not to do something, and confusing the line I'm typing on with red or blue highlights, suggestions. After I finish a draft, I can turn it back on and go through the suggestions to make the necessary fixes. I may do that with this blog...but not until I'm done with the draft.

(2) There's also a G icon in my dock called Grammarly Desktop. It contains several innocuous choices, but the one that actually makes sense is "Settings." Under Settings, you can view your Block List, Account Info, and Customization options. The Customization is extensive, but not enough for me. You can choose the style of English (US, Canadian, British, Australian, Indian), a Quick Key to accept suggestions, an Open shortcut keystroke, and the most useful "Writing Style." The writing style is a comprehensive list of proofing functions that you can turn on or off. See image for the first 1/5 of this list. This "Your preferences" list and your choices on it are kept at the G website and are served up live. You guessed it, if your internet connection goes down (even temporarily), G ceases to work well.

(3) The third control is in the Application Menu bar, e.g., Word. Which turns the G app on, if it had been off before. When it comes on, it searches your document and displays every grammatical issue you've requested, as per your preferences, in a sidebar. In my 57,000-word document, there were an estimated 1,800 suggestions to review. See sidebar (right). At the top, if you can read the details, you're told there are 366 alerts to check. There are growth bars for correctness (red), clarity (blue), engagement (green), and delivery (purple). All the alerts in the column below fall under one of these categories. As you see, my raw writing (the first 5 chapters of Tiger's Hope) scores high for clarity, engagement, and delivery, but poorly in correctness (meaning, grammar).

In the top right corner is the number 77 in a download circle. This is your score (out of 100). When I respond to each of the alerts in the list — either by accepting the correction, making a manual change to the manuscript, or dismissing the alert — that number has been 99 or 100.

Once I take one of those three actions to an alert, G automatically reevaluates the text, and may come back once or twice to offer a new suggestion, based on the change you made or didn't make.1. Their customer support exists, but it is not very helpful. Support (aside from a chatbot) is only available by filing a Support Ticket, and the email responses returned are boilerplate, simplistic answers, such as uninstalling and reinstalling. I've requested support 6 times, and I've finally given up on them. They never answer the question. And in the end, they've asked me to jump through hoops to compile a system report and send them the entire file, etc. I refused....too much time.

There are workarounds to issues you can learn. The biggest problem occurs when the Internet is slow or hesitant. During such times, the G system simply stops saving your changes and hangs up. I've managed to restart it by opening a previous file that had been through the G review, rebooting the entire computer, and then restarting G. Support suggests just quitting G and restarting.

3. When G for Mac is on, writing an email or blogging (as I'm doing now) is very difficult because G is constantly interrupting my writing with ways to write better. It's irritating

G for Mac alone will only check 4,000 files before it quits. Support says the word count is unlimited, but I cannot find an explanation of how I can invoke that capability . The web-browser version will check even fewer words at a time.

5. G for Word on Mac (an Add-in, they call it) will check 150,000 characters at a time, or about 30,000 words. For my 57,000-word novel, I split it into three files and recombined them when I was done. I've also been told by Support (contrary to what is printed on their website) that Word for Mac can check an unlimited number of words. However, this is coupled with the explanation that G only loads a certain number of words ahead of your cursor location, and once you move your cursor, G will load more words. This is only partly helpful. G can scan an entire file, but only if it's less than 150,000 characters. Within that limit, it can alert you to inconsistencies and help you make them consistent, like whether a word used throughout the document should be capitalized or not. If it's only checking part of the file, then you may not get all the words consistently capitalized.

6. I've been told by G-Support that G for Word on Mac is no longer going to be supported, OR it is no longer available for download. But the communication from their support is not always consistent. The personnel may be from a foreign country, and they may not understand English very well. That is ironic; support for an English grammar checking application is not provided by English grammar specialists.

7. G does not check quotation marks if they are missing. Sometimes it will adjust the closed quotation mark from before to after a period. But not always. G does not have a way to globally accept a similar alert throughout the document, like changing 70 ellipses without spaces between the periods to 70 ellipses with spaces between the periods. But that problem can be corrected directly in WORD using Advanced Search and Replace.

8. With G on and constantly checking, if it highlights a sentence you, and makes a suggestion, you better accept it, dismiss it, or close G and make a manual change. YOU CANNOT MAKE A MANUAL CHANGE TO A HIGHLIGHTED SUGGESTION. THE LOGIC WON'T LET YOU. Turn off the app first, else where you think you placed your cursor is NOT where you placed your cursor, and what you then type will be somewhere else. Good luck finding it.

Now that I'm mostly finished with this blog post I'll turn G for Mac back on and spend the next ___ minutes making "corrections.

SO WHAT CAN I TAKE FROM ALL THIS TO HELP WITH SABRIYA

Reviewing 1,800 grammatical and spelling suggestions:

a. Gave me a better understanding of grammatical constructions I'm weak at using

b. Corrected spelling issues I've misunderstood

c. Show me better ways to construct sentences that are easier to read, and use a greater variety of construction techniques.

Monday, July 7, 2025

SABRIYA Writing Journal 5: Starting to Write

You may note in the poster to the right that the picture of Sabriya has changed, and "Shanghai" has changed to "Shenzhen." More about that later.

The first scene of the first chapter (target 1,000 words) is supposed to set the tone and location of the story in an omniscient voice. According to Journal Entry 4, Step A, I had long pre-visualized the setting. So, I stepped to B. and began the "objective or universal POV" of the location and tone. This is what I came up with.

It was a wild boar snort before midnight, June 1995, when thirty-three thousand taxis and motorcycles jammed the streets, freeways, and ferries of Hong Chi. The colorful conveyances shuttled high-maintenance women from the crowded luxury shops of Chao and responsible men from the financial district back to their plastic kitchens and bamboo bedrooms in the banyan-festooned foothills. Meanwhile, young couples, apparently without responsibilities and dressed similarly, flocked to the club district and its frolicking nightlife, and male tourists, who had long ago shed their responsibilities, trooped to Qui Plaza’s red-light district where strumpets displayed their available assets for rent. Along the densely populated late-night streets, wet and muggy from a late-afternoon squall, the intoxicating mix of diesel exhaust and steam from food stalls hawking exotic stir-fries, kabobs, and crepes anesthetized the masses in their search for meaning.

EXCEPT, I had put off committing to a specific (historic) place. I really didn't want to get tangled up in writing another lengthy historical novel, because getting the history right is always challenging. "Hong Chi" sounded generic enough, and not like Bangkok or Hong Kong, where I'd face the historical challenges of also including the local political reality that always seemed in flux. But I faced a dilemma. I didn't want the story to be so generic that the culture could not be clearly identified. The story is about human trafficking, so I stopped writing 500 words into the 1,000, and started to read (again) about human trafficking and organ harvesting in SE Asia. It became apparent that China was at the top of the list, not just because of independent gangs, but because in the far north-western autonomous region of Xinjiang, there are reports of forced government organ harvesting of ethnic minorities.

Time and place are essential elements to nail down, so I've made a working choice. 1995. SHENZHEN. Shenzhen is a large, colorful Chinese city adjacent to Hong Kong. Shenzhen is located in the historically famous province of Guangdong, formerly known as Canton, where the Opium Wars took place along the Pearl River. I have read (twice) the non-fiction biography Canton Captain about Merchant Captain Robert Bennet Forbes (1804–1889) (written by James B. Connolly). I was fascinated by the place and wanted that research effort to play into the Sabriya project. Another inadvertent piece of research is that we have a close acquaintance who lives in China, who has visited Shenzhen and worked for the UN on anti-human trafficking projects.

Finally, as a visual person, I knew that I would need to physically describe my characters early on in the manuscript, and that their ethnic background would play a role in those descriptions. This realization led me to make decisions that pushed my desire for a generic approach off the table.

Here are the steps I've taken in the last few days.

MAP

I created a map and identified the location of all the major scenes in the treatment. Google Maps is very helpful here, especially since all the locations identified in the map below (yellow dots) have photo galleries accessible on Google Maps. So, I can see what the land and buildings look like as they have been photographed in the last few years.

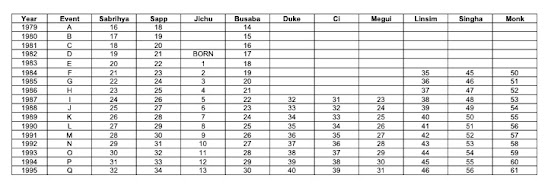

TIMELINE

Next, I had to nail down the historic events and ages of all the major characters in the story. The principal story takes place in 1995, before Hong Kong was handed over to the People's Republic of China (in 1997), marking the end of 156 years of British rule. For my story to work, the United Kingdom still needs clout in China. I've created timelines like this successfully in the past using Excel. The image below shows an example of the Excel timeline for Sibriya's story. It lists the central characters and their ages corresponding to events in the plot beginning in 1979. The last row is 1995. I will add political and other events to this Excel file as needed. (Yes, there are multiple story events each year, here represented simply by the letters A through Q.)

Tuesday, July 1, 2025

SABRIYA Writing Journal 4: Writing Rules

I've started to write, after many weeks of planning and plotting. Now, the rules of writing, for me, will vary day-to-day. Not that the rules change, but because I'll forget them from one day to the next. Thus the critical need for rewriting and remembering the rules.

MY WRITING RULES:

The following assume I've taken the time to outline the story, and completed due diligence in researching the broader aspects of the era and characters—both critical writing tasks, which in this case I've done. The rules below are not about general research, planning or plotting (see Journal entires 1-3) but about stringing the words together for the first time.

- VISUALIZE FIRST. Take time to visualize the scene as if watching a movie. This may be the most time consuming thing about writing—NOT WRITING.

- START OBJECTIVE. Every scene should begin with a paragraph from an objective or universal Point-of-View (POV) that describes the setting and characters in the scene with a disaster close at hand. By objective POV I mean the POV of someone NOT in the scene—the narrator—who can see everything about the scene, e.g. God's POV.

- ONE POV. After that first objective POV paragraph, every other paragraph in a scene must be told from a single character's POV who is IN THE SCENE, perhaps the POV of the most emotionally conflicted character.

- WRITE FOR IRONY. Every description, and perhaps line of dialogue, should contain an ironic comparison.

- WRITE TO TARGET. First draft not so much, but second draft must condense word count to the target number, OR revise the rest of the chapter or book so word count goal (overall) is observed.

- WRITE ATTITUDE. Write with an emotional attitude that channels the POV character. Nothing in this word is clean and objective. Even God has an attitude and sometimes he expresses with with catastrophic results. Attitudes vary from sarcasm to sweetness, from retribution to forgiveness. Vary the attitude as you vary the POV.

- END ON CLIFF. Every scene ends with a cliff hanger described by Step 3 (the disaster step) of the Scene-Sequel structure pattern. In some cases this may be an objective, universal POV, like the first paragraph of the scene. (more on Scene-Sequel below)

- RIGHT WORD. Never hesitate to take the time to find the right word, turn-of-phrase, or trope. (more on tropes below)

Scene-Sequel Structure Pattern

Writing in a Scene-Sequel pattern is method of structuring your writing at a paragraph, sentence, or micro level. If you deconstruct the best fiction writers' output, you will see it. I always start out writing a new project by following this pattern anally, by putting these hidden steps in Scrivener to constantly remind me. After a few weeks the pattern becomes almost automatic.

Running from left to right in the above diagram. (1) The protagonist has a physical GOAL to achieve. (2) The protagonist takes action to achieve that goal, and in so doing creates CONFLICT with the antagonist. (3) Because of the conflict, the goal is not fully achieved, resulting in a DISASTER. (4) The protagonist experiences an EMOTIONAL REACTION, which acts as a motivation to keep going. (5) The protagonist spends some time evaluating in his mind (THOUGHT) the DILEMMA faced, until... (6) The protagonist makes a decision about the next goal and takes the fist steps to achieve it. [And the process REPEATS starting with the new goal.]

Novel Scene-Sequel Sequence (simplified)

Tropes are recurring themes, ideas, or literary devices used in storytelling. They can be categorized into various types. Tropes can be elements of character, plot, or setting, and they often reappear in different stories, sometimes becoming defining characteristics of a genre.Here's a breakdown of some common types of literary tropes:

Metaphor: A comparison between two unlike things without using "like" or "as" (e.g., "Juliet is the sun").Simile: A comparison between two unlike things using "like" or "as" (e.g., "Her smile was like sunshine").Irony: A figure of speech in which words are used in such a way that their intended meaning is different from the actual meaning of the words (e.g., saying "Oh, fantastic!" when something bad happens).Synecdoche: A figure of speech in which a part is used to represent the whole (e.g., "wheels" for a car).Metonymy: A figure of speech in which one thing is used to represent something else with which it is closely associated (e.g., "the crown" for the monarchy).Hyperbole: Exaggeration used for emphasis or effect.Litotes: Understatement, often for ironic effect (e.g., saying "not bad" when something is actually very good).