I recently reviewed Paul Gulino's book "Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach." I found the book a bit obtuse and not clearly written, but Chris Soth (of ScreenwritingU) makes it easier to understand. Soth calls this structure the Mini-Movie Method (MMM).

This method of structuring a movie divides the story into 8 segments where Act 1, 2A, 2B, and 3 are all divided in half by events like the Inciting Incident, Pinch Points and the Final Incident, giving you, theoretically 8 equal parts.

Now, think of those eight segments of a movie, each 12.5% of the whole, as INDIVIDUAL movies or long sequences, each with a beginning, middle and end. Or 8 short movies strung together, each with a climax (the moment or turning point).

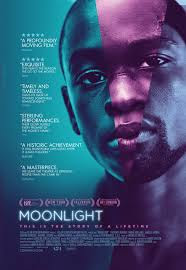

The 2016 Best Picture, MOONLIGHT, is constructed with three long sequences. The three parts tell the the coming of age story of a gay-black man raised in a poor, drug invested part of Miami. First, as a boy (called Little); second, as a teenager (called Chiron, his give name); and third, as an adult (called Black). The three sections are each preceded by a title card, simply:

i

Little

ii

Chiron

iii

Black

This simple and direct structure, made explicit to the audience, was one (of many) reasons the screenplay won an Screenwriting Oscar for BEST ADAPTATION.

So, what Gulino (and Soth) propose is that you divide your feature into 8 parts, two for each of the major 4 segments: Act 1, Act 2A, Act 2B, and Act 3. These 8 parts are the same segments (less the Prologue and Denouement) you'll see on my StoryDiamond or on the linear representation of a Story's 13-20 Beats --- both represented below in miniature. (Click on the links above for posts that explain. And, click on any diagram for a larger version, that you can actually read.)

[BTW: I have updated the StoryDiamond again, and for the first time in six years edited and updated the Annotation or Notes Document that goes with it. If you use the Story Diamond I encourage you to download the latest at the links herein.]

Now, here's the new thing I came away with. If we think of each of these 8 segments, or sequences, or mini-movies as each having a goal that the protagonist needs to achieve, then it's like you have 8 subplots, which run sequentially, as opposed to most subplots that run in parallel. Here's a diagram I crafted. Below the diagram is a further explanation. (You can click on any image to make it bigger.)

Now, here's the new thing I came away with. If we think of each of these 8 segments, or sequences, or mini-movies as each having a goal that the protagonist needs to achieve, then it's like you have 8 subplots, which run sequentially, as opposed to most subplots that run in parallel. Here's a diagram I crafted. Below the diagram is a further explanation. (You can click on any image to make it bigger.)

1. One good way to hook your audience is that each of the sequences has a goal. Let's call the first seven, "subgoals," as the end point of each of the subplots. (In the digram, the subgoals are symbolized by the red stars). The story must be constructed in such a way that each subgoal MUST be achieved before the next subplot can be engaged, and the next subgoal be achieved. That is, the first subgoal is logically nested (and its resolution more or less resolved) before the second subgoal can be pursued and achieved. This is very much like a video game (which I don't play) where to get to the end of the game you have to acquire all the earlier magic lanterns, or pots of gold along the way. If you miss one, you stop dead in your tracks.

The trick is to construct a story where the eight subplots and subgoals are logically dependent, nested and chronologically sequential. The later goals all have to be subservient to the earlier goals. (Soth used INDIANA JONES AND THE LOST ARK as an example.) And in movies like THE LOST ARK you can even think of each of the 8 subplots with their attending subgoals as "set pieces" or locations. So, you have a 11 minute adventure in one wilderness location, there's a 1.5 minute climax where the protagonist finds some level of defeat and that propels him or her to the next set piece and the next sequence. Come to think of it the James Bond movies are pretty well structured like that.

2. Of course, each of the subgoals MUST support the final main goal. This is what I teach about subplots (that run in parallel) and their subgoals—e.g. every subplot goal must be related to the single moral premise, and the virtues and vices associated with it. That is, every subplot has to struggle with the same conflict of values, but perhaps in a different way. In Gulino's Sequences (and Soth's Mini-Movies) the subplots are sequential, and logically dependent. This is brilliant.

3. The process suggests that just after each goal is achieved, there is an increasingly terrible and epic failure on the part of the protagonist, which causes his hopes to descend into fear. According to the Moral Premise theology (yeah, I should start a religion), these immediate descends are the consequence of two related forces: (1) the action of the antagonist, and (2) the weakness of the protagonist, which is a milder form of the powerful vice exerted by the antagonist.

Do I need to point out the emotional roller-coaster effect this creates? Alas, one of my bully pulpits.

Do I need to point out the emotional roller-coaster effect this creates? Alas, one of my bully pulpits.

This perfectly follows an age-old concept of novel writing—in every scene-sequel sequence there is a DISASTER that spurs the action forward (or in a new direction...a mini-turning point). Here's a diagram from my on-line workshop (Storycraft Training). An explanation follows.

|

| Novel Scene-Sequel Sequence (simplified) |

Running from left to right in the above diagram. (1) The protagonist has a physical GOAL to achieve. (2) The protagonist takes action to achieve that goal, and in so doing creates CONFLICT with the antagonist. (3) Because of the conflict, the goal is not fully achieved, resulting in a DISASTER. (4) The protagonist experiences an EMOTIONAL REACTION, which acts as a motivation to keep going. (5) The protagonist spends some time evaluating in his mind (THOUGHT) the DILEMMA faced, until... (6) The protagonist makes a decision about the next goal and takes the fist steps to achieve it. [And the process REPEATS starting with the new goal.]

Now, I've added a couple of things from my other workshop sessions (c.f. Storycraft Training). Let me repeat the diagram for ease of reference.

4. Each sub goal has to be harder to achieved, and the conflict and tension associated with its accession has to be higher than the last subplot and goal. I have gradated the vertical scale into +8 and -8 levels.

5. Likewise the disasters (represented by the black dos) are increasing terrible. Thus, the goals and the disasters, get farther and farther apart, creating an escalating emotional roller coaster. the dipole here is HOPE vs. FEAR—a good way to convey it on an emotional level, which for a story is critical. Of course there are other ways to define the roller coaster, e.g. rationally (Is the protagonist progress toward the goal progressing or retarding?), and/or morally (Is the essential truth of the moral being tested true or false?)

6. Lastly, going back to my earlier description of the 13-20 beats, the Turning Points and the Pinch Points have a characteristic difference in how each of those seven disasters occur. The odd number disasters (above, i.e. 1, 3, 5, 7) are initiated or caused by the antagonist's power, whereas the even number disaster (above, i.e. 2, 4, and 6) are caused by the protagonist's weakness, blindness, and poor judgement.

Comments?