Over the past week, I've been forced to take a break from Sabriya of Shenzhen to make progress on another novel... the one before Sabriya—Tiger's Hope.

I've titled this post 'Sabriya...', however, and not 'Tiger', to illustrate an essential aspect of a writer's life—life is full of interruptions and is really only a stepping stone for the current project.

That means the diversion to work on Tiger's Hope must and inevitably will advance Sabriya's progress.

How did that work out for me?

Tiger's Hope is a 57,000-word novel based on a screenplay we almost produced a decade ago. I've blogged about this earlier. After finishing the draft and reading it aloud to ensure the structure and plot flowed smoothly, I was ready to have it proofread.

My regular proofreader was free (my sister, the editor), but I've overworked her, she's busy this summer, and this novel didn't interest her that much. I had no problem with that.

I've been fortunate to work with a half-dozen proofreaders over the years. None of them were perfect. Even with my bad grammar skills, I was still finding things they missed. I was worried that since G missed the error, it might miss even more, and I would never find what was missed. On Wizard Clip Haunting, there were four editors, and each one saw more and more things wrong. It was disheartening.

Okay, so let's hire a "professional."

Proofreaders for a 57,000-word novel cost from 0.7 to 1.5 cents per word, or $400 to $855. That's reasonable. I queried the $400 proofer. She was not taking on any more work...which translates to, "I've underpriced my services."

Next, a $650 proofreader might have been able to review my novel in about three months. I was not willing to wait that long.

All this time, I was thinking about how I needed a foolproof way to look at every comma, every sentence with cold, calculated eyes... when the word algorithm came to mind. That meant computer, and that suggested A.I.

I'm not in favor of AI-generated text. When an author uses it to generate text, it's not the writer, and it makes sense that what I've read is true—a writer who uses AI to write can't remember what "he" wrote. So, what good is it to him? That probably reveals that I'm not very well off financially. My goal is not to make money, but to learn and instruct, so that I can know even more. I'm repulsed by all the "get rich quick" memes on social media about having an AI generator write a book and the "writer" collecting the royalties. Sorry, I find that repulsive and right up there with fake news.

However, I have no problem with a computer pointing out that I've misspelled a word or that my grammar could be improved.

After a day of researching AI proofing tools, although not in-depth, I chose Grammarly. As I suspected, it wasn't perfect and over the entire book (I finished Grammarly's proofing of the 57,177 words last night), I manually rejected about 50% of its "corrections." So, here's a review of my findings. And to cut to the chase, I believe the novel is significantly improved after using Grammarly than it was before.

SETUP NOTES and CONTROLS

MY COMPUTER

I work with Microsoft Word at this stage (after I draft in Scrivener). I am working on a 2015 Power Mac (tower) running macOS Monterey (12.7.6). I have two 27" displays. While I'm surrounded by RAID 1, 2T–16T external ThunderPort drives, my manuscript writing is done on the system's 1T Solid-State Memory. I've discovered that MS Word does not like to save files to an external drive without creating a temporary file to work on. After an hour's work, I realize I've been typing into a Word Temporary file with an incomprehensible file name that can't be found without using 'Save As'...

GRAMMARLY (G)

I installed G-Pro ($12/month) on my Mac, including Grammarly for Mac and Grammarly for Word. There is also a web browser version, but it does not allow me to preserve my Word Styles and other formatting. On my computer, two versions may conflict, and G's Support team keeps advising me to turn one off or uninstall it due to issues that arise. I tried that once, but rejected it for the reasons cited below.

There are actually three G controls on my desktop:

(1) In the Mac Tab bar at the very top of my primary screen. It's a pull-down menu that allows me to turn G on or off for different applications. Currently, it is off. When it's on, it's like a grammar teacher constantly looking over your shoulder and telling you not to do something, and confusing the line I'm typing on with red or blue highlights, suggestions. After I finish a draft, I can turn it back on and go through the suggestions to make the necessary fixes. I may do that with this blog...but not until I'm done with the draft.

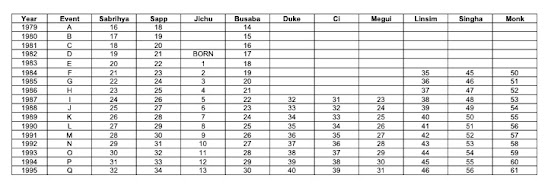

(2) There's also a G icon in my dock called Grammarly Desktop. It contains several innocuous choices, but the one that actually makes sense is "Settings." Under Settings, you can view your Block List, Account Info, and Customization options. The Customization is extensive, but not enough for me. You can choose the style of English (US, Canadian, British, Australian, Indian), a Quick Key to accept suggestions, an Open shortcut keystroke, and the most useful "Writing Style." The writing style is a comprehensive list of proofing functions that you can turn on or off. See image for the first 1/5 of this list. This "Your preferences" list and your choices on it are kept at the G website and are served up live. You guessed it, if your internet connection goes down (even temporarily), G ceases to work well.

(3) The third control is in the Application Menu bar, e.g., Word. Which turns the G app on, if it had been off before. When it comes on, it searches your document and displays every grammatical issue you've requested, as per your preferences, in a sidebar. In my 57,000-word document, there were an estimated 1,800 suggestions to review. See sidebar (right). At the top, if you can read the details, you're told there are 366 alerts to check. There are growth bars for correctness (red), clarity (blue), engagement (green), and delivery (purple). All the alerts in the column below fall under one of these categories. As you see, my raw writing (the first 5 chapters of Tiger's Hope) scores high for clarity, engagement, and delivery, but poorly in correctness (meaning, grammar).

In the top right corner is the number 77 in a download circle. This is your score (out of 100). When I respond to each of the alerts in the list — either by accepting the correction, making a manual change to the manuscript, or dismissing the alert — that number has been 99 or 100.

Once I take one of those three actions to an alert, G automatically reevaluates the text, and may come back once or twice to offer a new suggestion, based on the change you made or didn't make.1. Their customer support exists, but it is not very helpful. Support (aside from a chatbot) is only available by filing a Support Ticket, and the email responses returned are boilerplate, simplistic answers, such as uninstalling and reinstalling. I've requested support 6 times, and I've finally given up on them. They never answer the question. And in the end, they've asked me to jump through hoops to compile a system report and send them the entire file, etc. I refused....too much time.

There are workarounds to issues you can learn. The biggest problem occurs when the Internet is slow or hesitant. During such times, the G system simply stops saving your changes and hangs up. I've managed to restart it by opening a previous file that had been through the G review, rebooting the entire computer, and then restarting G. Support suggests just quitting G and restarting.

3. When G for Mac is on, writing an email or blogging (as I'm doing now) is very difficult because G is constantly interrupting my writing with ways to write better. It's irritating

G for Mac alone will only check 4,000 files before it quits. Support says the word count is unlimited, but I cannot find an explanation of how I can invoke that capability . The web-browser version will check even fewer words at a time.

5. G for Word on Mac (an Add-in, they call it) will check 150,000 characters at a time, or about 30,000 words. For my 57,000-word novel, I split it into three files and recombined them when I was done. I've also been told by Support (contrary to what is printed on their website) that Word for Mac can check an unlimited number of words. However, this is coupled with the explanation that G only loads a certain number of words ahead of your cursor location, and once you move your cursor, G will load more words. This is only partly helpful. G can scan an entire file, but only if it's less than 150,000 characters. Within that limit, it can alert you to inconsistencies and help you make them consistent, like whether a word used throughout the document should be capitalized or not. If it's only checking part of the file, then you may not get all the words consistently capitalized.

6. I've been told by G-Support that G for Word on Mac is no longer going to be supported, OR it is no longer available for download. But the communication from their support is not always consistent. The personnel may be from a foreign country, and they may not understand English very well. That is ironic; support for an English grammar checking application is not provided by English grammar specialists.

7. G does not check quotation marks if they are missing. Sometimes it will adjust the closed quotation mark from before to after a period. But not always. G does not have a way to globally accept a similar alert throughout the document, like changing 70 ellipses without spaces between the periods to 70 ellipses with spaces between the periods. But that problem can be corrected directly in WORD using Advanced Search and Replace.

8. With G on and constantly checking, if it highlights a sentence you, and makes a suggestion, you better accept it, dismiss it, or close G and make a manual change. YOU CANNOT MAKE A MANUAL CHANGE TO A HIGHLIGHTED SUGGESTION. THE LOGIC WON'T LET YOU. Turn off the app first, else where you think you placed your cursor is NOT where you placed your cursor, and what you then type will be somewhere else. Good luck finding it.

Now that I'm mostly finished with this blog post I'll turn G for Mac back on and spend the next ___ minutes making "corrections.

SO WHAT CAN I TAKE FROM ALL THIS TO HELP WITH SABRIYA

Reviewing 1,800 grammatical and spelling suggestions:

a. Gave me a better understanding of grammatical constructions I'm weak at using

b. Corrected spelling issues I've misunderstood

c. Show me better ways to construct sentences that are easier to read, and use a greater variety of construction techniques.